|

|

- Search

| J Acute Care Surg > Volume 11(1); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The severity of a patient’s medical condition, changing pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, and variability in medication highlight the importance of pharmacological intervention by intensive care unit (ICU) specialized pharmacists.

Methods

Retrospective observations of ICU interventions (omission, changes in medicine, side effects, changes in administration route and dosage, redundancy, and nutritional care) performed between April 2017 and March 2018, determined by an interdisciplinary team (including a specialized ICU pharmacist and a surgical intensivist) on their surgical ICU round, were analyzed. Medicinal prescriptions were screened weekly during the surgical ICU round, and interventions were made if any corrections were necessary. Two days later another team including a surgical intensivist, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist evaluated the patients’ nutritional status (performed weekly).

Results

In the 23-bed ICU, the average number of patients whose prescriptions were examined was 22.38 per surgical round. There were 382 interventions made over 1 year, which was 9.68 interventions per day. The interventions were for nutritional care (161 cases, 42.2%), followed by changes in administration route and dosage (94 cases, 24.6%), omission (59 cases, 15.5%), redundancy (40 cases, 10.4%), changes in medicine (15 cases, 3.9%), and side effects (13 cases, 3.4%).

Conclusion

The conditions of patients admitted to ICU are typically unstable. Pharmacological interventions suggested by a specialized pharmacist may help control the changing medical condition of patients in ICU. A higher participation of pharmacists specialized in working in an interdisciplinary ICU team-based system could lead to safer treatments.

Patients are admitted to intensive care units (ICU) when they are in a critical condition requiring constant observation to monitor vital signs and need specialized care for life support and organ failure. Invasive hourly monitoring procedures and life support comprises of invasive mechanical ventilation, application of vasopressors, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or continuous renal replacement therapy [1]. Several medications are administered to a single patient and the dosage of each medication differs according to an individual’s age and medical condition [2,3]. Medication errors are inevitable even though physicians pay more attention to prescriptions for ICU patients, the necessity for screening and intervention of prescriptions has long been emphasized [4]. Medication error may occur while managing rapidly deteriorating or acutely exacerbating patients, by omitting some drugs, or mistaking administration routes, or dosage. Not only can a pharmacist screen for and correct these mistakes, but also use their professional knowledge about drug-drug interactions due to multidrug administration, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, in taking care of critically ill patients [5].

Several medical centers already have pharmacists participate in ICU rounds or work exclusively in ICU [6–10]. Some hospitals have given positive feedback and the results of pharmacists’ intervention on the prescription of drugs for ICU patients [11–13]. Therefore, in this study, groups of pharmacists, and nutritionists were asked to participate in multidisciplinary surgical ICU rounds with surgical intensivist from April 2017, to review prescriptions. Here we report the incidence of medical errors and interventions made through interdisciplinary rounds.

A retrospective observational study of all the prescriptions made for patients being treated in a surgical ICU (23-bed) was conducted from April 2017 to March 2018. Patients in the surgical ICU mainly required neurosurgery, general surgery, cardiac surgery, and a few patients required otolaryngology, urology, obstetrics and gynecology, and internal medicine.

A pharmacist was assigned to work in the ICU, and participated in medical rounds with a surgical intensivist every Tuesday (10:00 to 12:00). The pharmacist checked admission date, diagnoses, reason for admission to the ICU, medications administered in the past week, laboratory results, administration of drugs that required therapeutic drug monitoring. Prescriptions were examined based on Order Communicating System to evaluate if the medicines prescribed were optimal and the appropriate dosage and method of administration were being used. If there were any corrections to be made (as observed during the surgical round), direct contact was made by the surgical intensivist to the resident in charge, to relay the information that an order needs to be modified, or that the surgical intensivist had already made the modification.

Another team including the surgical intensivist, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist evaluated the patient’s nutritional status every Thursday (13:00 to 15:00). Both the pharmacist and the surgical intensivist were members of Nutritional Support Team of the hospital.

A written report on the analysis of interventions was made which included the number of corrections, frequency, and correction details (follow-up-monitoring was regularly performed to make sure that the interventions were reflected after the day of the initial correction). The details of the intervention were classified in 6 categories: 1) Omission error, 2) changes and addition in medicine (for better efficacy), 3) changes due to side effects, 4) nutritional care, 5) administration route and dosage error, and 6) redundancy error.

Interdisciplinary rounds for the 23-bed surgical ICU were performed every Tuesday and Thursday, and an average of 22.38 patients’ prescriptions were examined on each day. The total number of pharmacological interventions was 382 for a year, which is about 9.7 interventions per day.

Among the interventions made, the number of nutritional corrections was 161 (42.2%), changes in administration route and dosage 94 (24.6%), prescription omission 59 (15.5%), prescription redundancy 40 (10.4%), changes in medicine 15 (3.9%), and changes due to side effects 13 (3.4%; Table 1). The number of interventions decreased in the months where staff holidays were taken.

Of the nutritional interventions, most of the cases (44/161, 27.3%) were for cases where there had been multivitamin or trace element omission for those who were nothing by mouth (NPO) and required total parenteral nutrition. For 41 cases (25.5%), the number of calories administered to a patient was insufficient, while in 26 cases (16.1%) too many calories had been given. Some patients who thought to be in a poor nutritional state had undergone serological testing for vitamin and trace element including zinc, copper, manganese, selenium, and vitamin D levels. For those whose blood test results were low in levels of vitamins or trace elements, supplements were prescribed (13 cases, 8.1%). There were 37 other cases for which the recommendation was electrolyte-free total parenteral nutrition solutions (for patients with a severe, chronic electrolyte imbalance, or had been on amino acid or lipid-only nutritional admixtures), or discontinuation of antacids or proton pump inhibitors (for patients who started oral feeding; Figure 1).

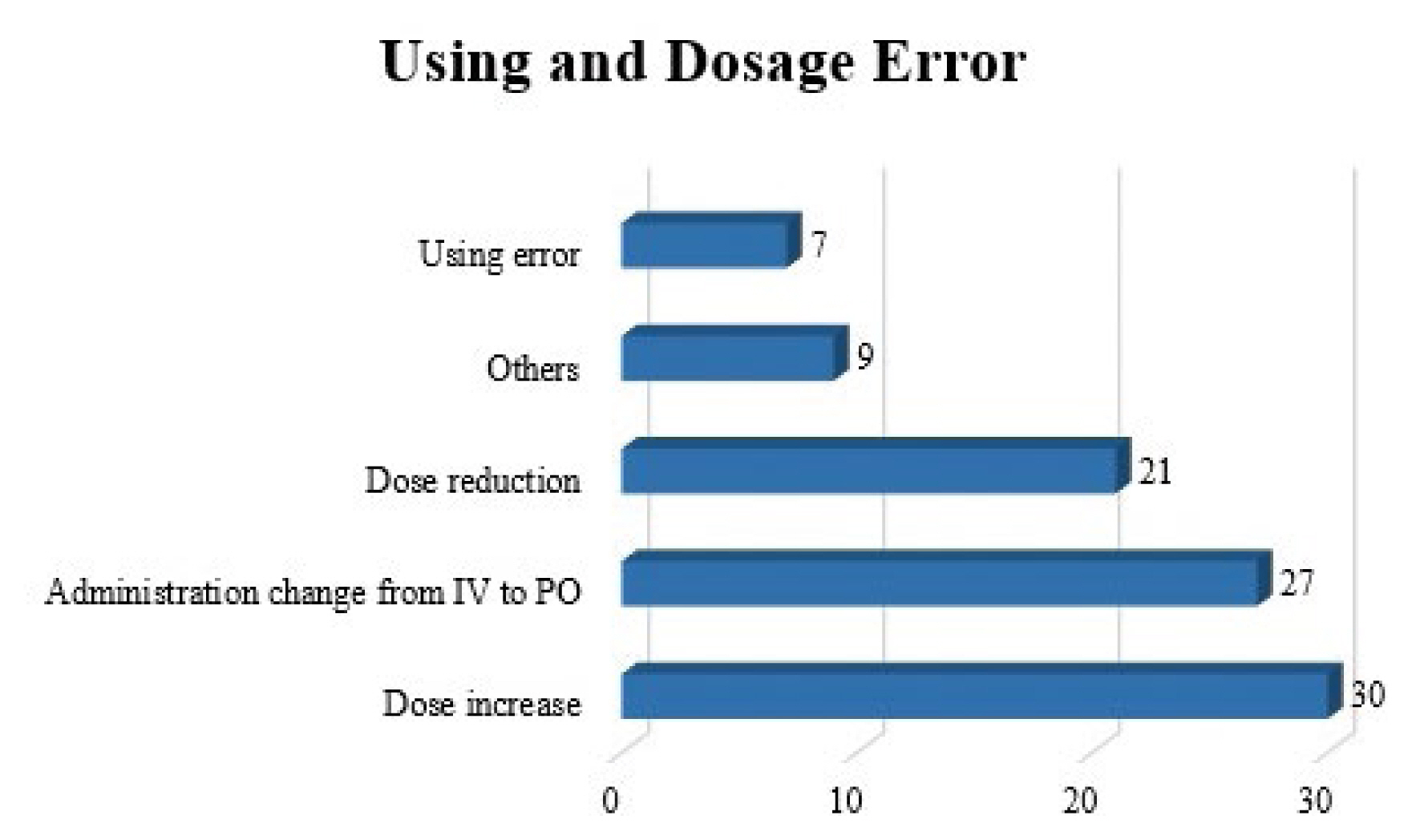

Changes in administration route and dosage accounted for 94 cases, of which there were 30 (31.9%) for dose increments, 27 (38.7%) for changing routes of administration from injected (any kind) to oral route, 21 (22.3%) for dose decrements, 7 (7.5%) for errors in administration routes (e.g., prescribing an inhalation drug for nasal administration, or prescribing a rectal capsule intended for oral route). There were 9 other cases (9.6%) where a recommendation was made for the addition of medication due to an elevated liver function test result. The prescription of metoclopramide was limited according to the safety recommendation, or by adjusting administration timings due to drug-drug interaction between almagate and other drugs (Figure 2).

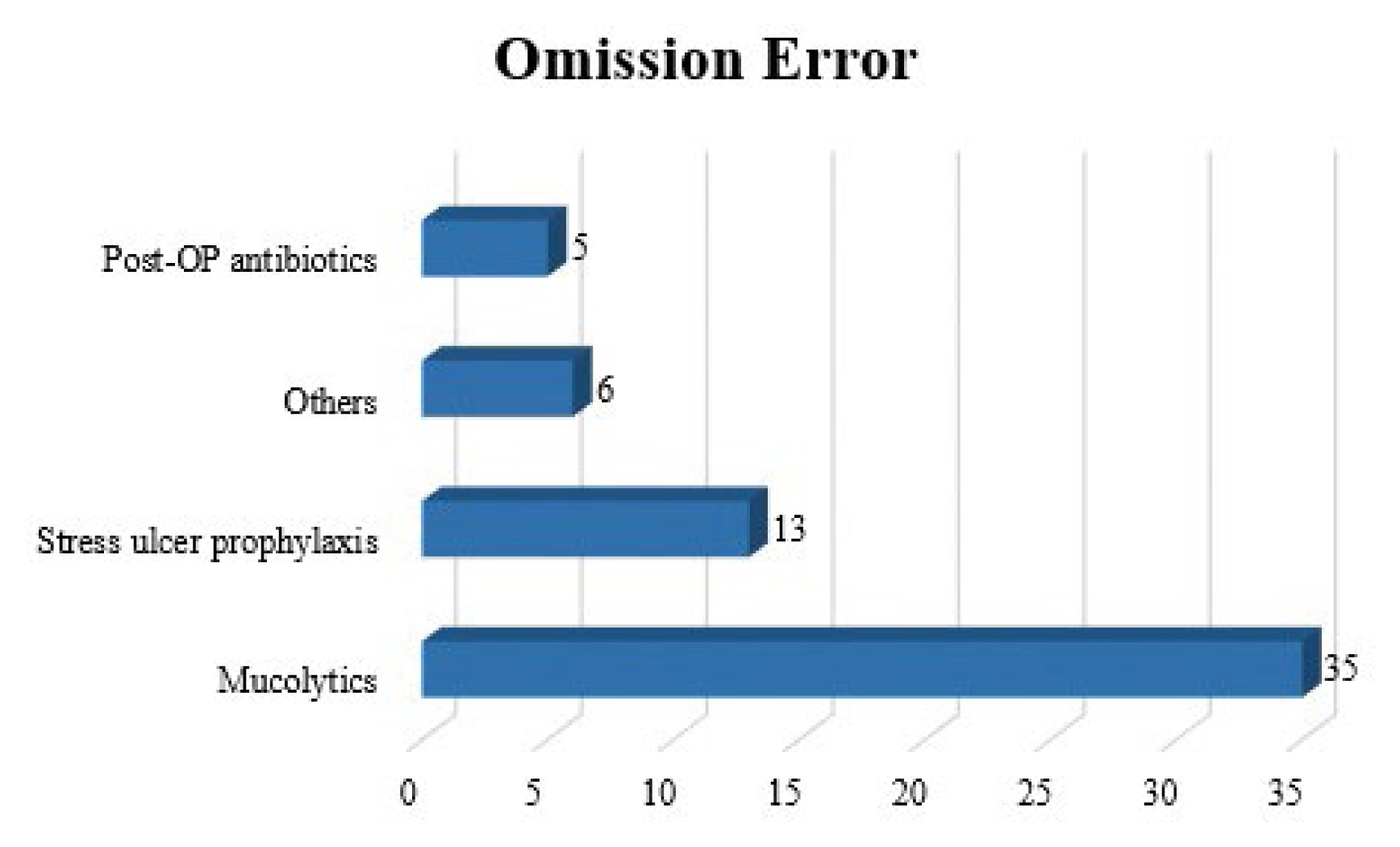

There were 59 omitted prescription cases including mucolytics for patients who were on mechanical ventilation care (35, 59.4%), antacids to prevent stress-ulcers for patients who were NPO, and patients receiving post-operative antibiotics. There were 6 others (10.2%) where it was recommended that therapeutic drug monitoring levels or adding diluting solution to prescription was checked (Figure 3).

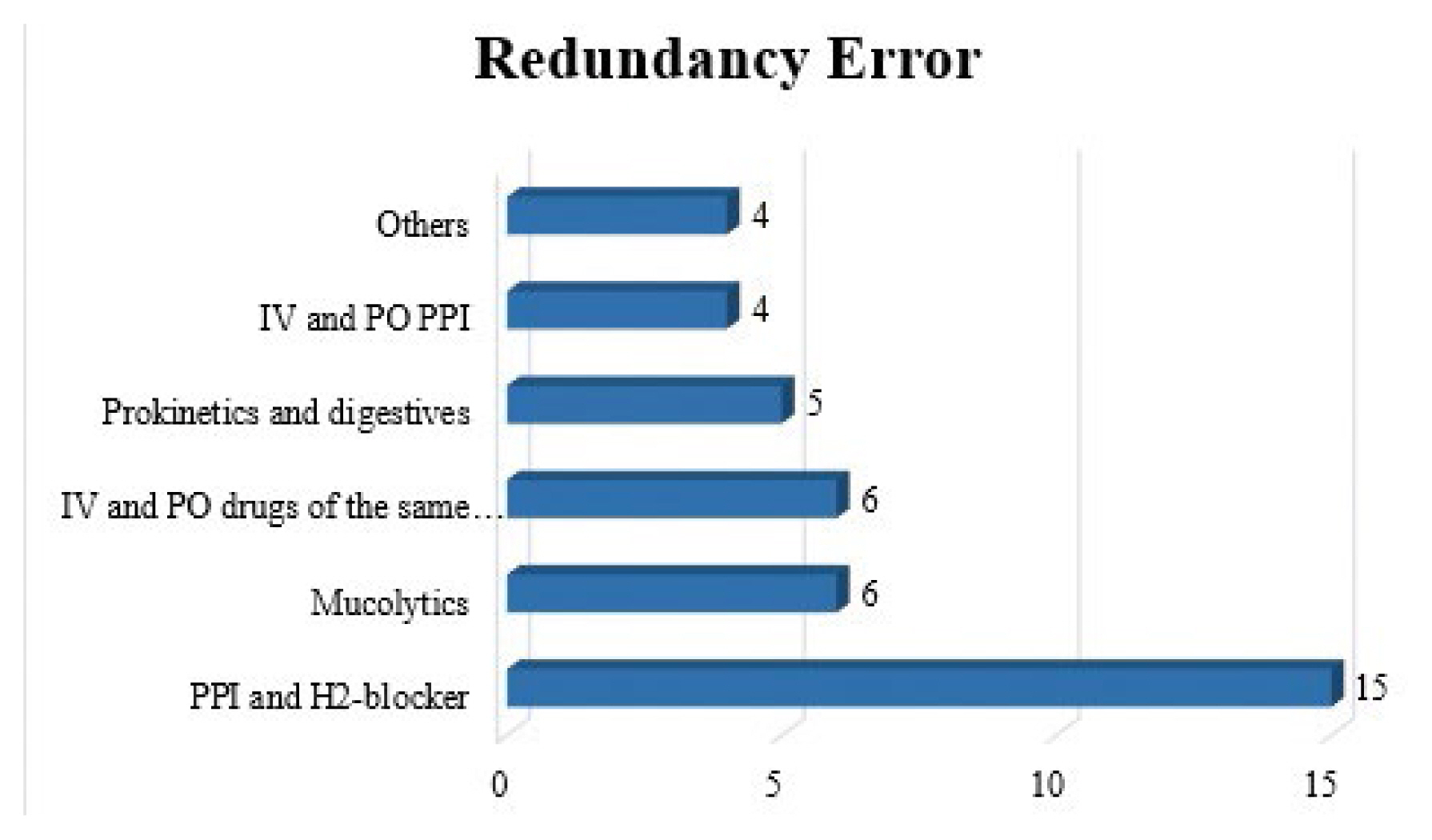

There were 40 interventions for prescription redundancy. The most common redundancy was prescribing both a proton pump inhibitor and a H2-blocker for stress ulcer prophylaxis (15 cases, 37.5%). There were 6 cases (15.0%) of prescribing drugs which had the same active ingredients administered via 2 different routes (mostly intravenous and oral route). Several drugs of similar effects were prescribed simultaneously: mucolytics, digestives, and both intravenous and oral proton pump inhibitors, 6, 5, 4, cases respectively. There were 4 other cases where prescribing both the 1st and 3rd generation cephalosporin occurred, or prescribing diluting solution for premixed medications (Figure 4).

Patients admitted to ICU need far more focused care and frequent check-ups due to their critical health condition [14]. Essential medications for ICU patients comprises of mucolytics (for those on mechanical ventilation or at high risk of atelectasis after waking from general anesthesia), or medications to prevent stress ulcers (for those who are critically and chronically ill, NPO for a long period of time, or patients whose expected stay in ICU is lengthened) [15]. Besides these considerations, the health status of ICU patients is rapidly changing, for which health care workers should make the appropriate adaptation. For example, if a patient is wearing a nasogastric tube, drugs prepared in powder form i.e., tablets, should be preferential over intravenous injections [16].

Physicians pay more attention to critically ill patients and are willing to devote extra time into taking care of them. However, health care workers face heavy workloads and fatigue due to a shortage of manpower in the medical setting. This may lead to medication errors either due to lack of knowledge or experience, or simply because of human error [17]. Therefore, assessments were made to detect and correct medication error during interdisciplinary surgical rounds including a pharmacist and a nutritionist. Moreover, clinical efficacy of interdisciplinary surgical rounds was examined to determine if pharmacological interventions led to safer and more accurate treatment.

Pharmacological evaluations were made during the surgical rounds which were held every Tuesday morning. The surgical intensivist and pharmacist reviewed nutritional orders as well as medicinal orders. Main review points for nutritional care were focused on correcting multivitamin, trace elements, and total parental nutrition based on electrolyte level or caloric and protein requirements. A separate nutritional round was held every Thursday afternoon including a surgical intensivist, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist. The same pharmacist participated in the weekly nutritional rounds. Nutritional corrections were monitored to determine whether the recommendations from 2 days ago were actually applied to the patients. Furthermore, patients eligible for, or already on enteral feeding were assessed to ensure that their caloric requirements and supplement nutritional needs were met.

This study showed that the most common intervention made was the omission of multivitamin or trace element prescriptions for people (44 cases) who were on total parenteral nutrition. It has been reported that residents generally are lacking in comprehension about nutrition, especially around considerations of essential nutritional requirements other than the 3 essential nutrients (carbohydrates, protein, and fat) necessary for patients who are NPO despite the guidelines available [18–20]. Besides, overnutrition, and undernutrition there were 67 cases where patients’ composition of diet or total parenteral nutrition was adjusted. Undernutrition was noted in patients that underwent both enteral feeding (either by oral route or nasogastric tube) and supplemental parenteral nutrition. This revealed that physicians have little knowledge of the total number of calories being delivered to the patient or of the amount of daily required proteins. In case of trace elements, similar medications were prescribed redundantly or the same medication was prescribed 2 to 3 vials at a time. The study shows that doctors should be enlightened to the importance and necessity of trace elements, and they also should be informed of the appropriate administration route and dosage.

In changes of administration route and dosage, the most common cases were correcting antibiotic doses according to creatinine clearance levels. However, recent studies have reported that without using the creatine clearance method to determine antibiotics levels is inadequate in ICU patients. Appropriate dosing of antibiotics was discussed each time with the clinicians when the dosage of antibiotics was too high or low. The correction was made only when clinicians were aware of their patients’ creatinine clearance. Similar corrections were made for medication errors that did not take creatinine clearance into account when prescribing drugs with nephrotoxicity. Daily blood tests in the morning included serum creatinine level, but sometimes doctors missed checking the results as patients’ health condition worsened. Recommendations for dosage adjustments were made in these cases.

Marked mistakes were of frequency of dosing due to writing errors. Since these simple mistakes are inevitable despite meticulous care, scrutiny at multiple levels (e.g., primary surveillance by nurses, secondary within a clinical department, and tertiary examination by interdisciplinary rounds) ensures safe delivery and medicinal administration. Omission errors originating from oblivion also suggests close checks should be made on a regular basis. On the contrary, redundancy error mostly arose from a lack of understanding of the mechanism of action and effect of a medicine [26].

These errors are also seen in studies performed in other ICU settings [6,8,26]. The types and frequency of errors are comparable with those observed during this current study. Even though an exact comparison is not applicable since each study classified medication errors differently, the tendency was that omission errors followed by dosage errors with minimal difference led to types of errors [6,8,26]. This study was unique in that nutritional consideration was taken into account when most studies separated nutrition issues from medication errors.

Improvements to better treatment and safer medicinal delivery can be made through establishing a structured network system where healthcare workers can share knowledge and make revisions [27,28]. Firstly, lists of ICU mandatory medicine should be defined and made as a prescription bundle. By looking up which medications are necessary, physicians would make less omissions and redundancies in prescribing medication. Secondly, mutual accessibility between clinical pharmacists and physicians should be made easier. Just as pharmacists report to doctors on a regular basis, and when needed, suggest whether medicines are appropriately administered, better consultations will be made if physicians have access to pharmacists specialized in ICU management. Thirdly, the importance and necessity of ICU pharmacists should be recognized and supported by a legitimate system, entrusting them to supervise prescription, administration, and return of medicines.

This study has several limitations to acknowledge. The study population was selected from only a single surgical ICU from a single medical center. The interdisciplinary surgical round was performed for a short period of time (2 hours). Comprehensive analysis could have been performed if data were collected both before and after the initiation of interdisciplinary surgical rounds. Prescription errors were not officially recorded and collected before April 2017 therefore the study was restricted to 1 year. Due to lack of manpower, surgical rounds for prescriptions were performed only once a week. Among many clinical departments whose patients were admitted to the surgical ICU, some had the wrong bundle prescriptions that physicians repeatedly used, and it may have led to multiple similar interventions. Yet, various corrections were made through interdisciplinary surgical rounds that ultimately resulted in an improved quality of treatment and management of patients.

It is expected that there would be a safer level of care for ICU patients if interdisciplinary surgical rounds are implemented more frequently, more medical centers adopt this system, and if communication between pharmacists and physicians is encouraged and facilitated based on efficient and systematic contact program. The significance of interdisciplinary interventions regarding prescriptions should be acknowledged in order to establish a system where ICU patients are managed more carefully.

Figure 1

Number of pharmacological interventions for nutritional care.

TE = trace element; MV = multivitamin; others = electrolyte-free total parenteral nutrition solutions or discontinuation of antacids or proton pump inhibitors.

Figure 2

Number of pharmacological interventions for administration route and dosage error.

IV = intravenous; PO = per oral.

Figure 3

Number of pharmacological interventions for an omission error.

OP = post-operative; others = therapeutic drug monitoring levels or adding diluting solution to the prescription.

References

1. Nates JL, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, Blosser S, Goldner J, Birriel B, et al. ICU Admission, Discharge, and Triage Guidelines: A Framework to Enhance Clinical Operations, Development of Institutional Policies, and Further Research. Crit Care Med 2016;44(8):1553–602.

2. Mahmoud SH, Shen C. Augmented Renal Clearance in Critical Illness: An Important Consideration in Drug Dosing. Pharmaceutics 2017;9(3):36.

3. MacFie CC, Baudouin SV, Messer PB. An integrative review of drug errors in critical care. J Intensive Care Soc 2016;17(1):63–72.

4. Blum KV, Abel SR, Urbanski CJ, Pierce JM. Medication error prevention by pharmacists. Am J Hosp Pharm 1988;45(9):1902–3.

5. Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, Burdick E, Demonaco HJ, Erickson JI, et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA 1999;282(3):267–70.

6. Langebrake C, Ihbe-Heffinger A, Leichenberg K, Kaden S, Kunkel M, Lueb M, et al. Nationwide Evaluation of Day-to-Day Clinical Pharmacists’ Interventions in G erman Hospitals. Pharmacotherapy 2015;35(4):370–9.

7. Langebrake C, Hilgarth H. Clinical pharmacists’ interventions in a German university hospital. Pharm World Sci 2010;32(2):194–9.

8. Klopotowska JE, Kuiper R, van Kan HJ, de Pont A-C, Dijkgraaf MG, Lie-A-Huen L, et al. On-ward participation of a hospital pharmacist in a Dutch intensive care unit reduces prescribing errors and related patient harm: an intervention study. Crit Care 2010;14(5):R174.

9. Johansen ET, Haustreis SM, Mowinckel AS, Ytrebø LM. Effects of implementing a clinical pharmacist service in a mixed Norwegian ICU. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2016;23(4):197–202.

10. Jiang S-P, Zheng X, Li X, Lu XY. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical care in an intensive care unit from China. A pre-and post-intervention study. Saudi Med J 2012;33(7):756–62.

11. Lee H, Ryu K, Sohn Y, Kim J, Suh GY, Kim E. Impact on Patient Outcomes of Pharmacist Participation in Multidisciplinary Critical Care Teams: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med 2019;47(9):1243–50.

12. Kessemeier N, Meyn D, Hoeckel M, Reitze J, Culmsee C, Tryba M. A new approach on assessing clinical pharmacists’ impact on prescribing errors in a surgical intensive care unit. Int J Clin Pharm 2019;41(5):1184–92.

13. Bertels J, Almoudaris AM, Cortoos P-J, Jacklin A, Franklin BD. Feedback on prescribing errors to junior doctors: exploring views, problems and preferred methods. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35(3):332–8.

14. Cullen DJ, Sweitzer BJ, Bates DW, Burdick E, Edmondson A, Leape LL. Preventable adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: a comparative study of intensive care and general care units. Crit Care Med 1997;25(8):1289–97.

15. Marino PL. Marino’s the ICU Book. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

16. Beckwith MC, Feddema SS, Barton RG, Graves C. A guide to drug therapy in patients with enteral feeding tubes: dosage form selection and administration methods. Hosp Pharm 2004;39(3):225–37.

17. Wittich CM, Burkle CM, Lanier WL. Medication errors: an overview for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89(8):1116–25.

18. Kreymann K, Berger M, Deutz Ne, Hiesmayr M, Jolliet P, Kazandjiev G, et al. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr 2006;25(2):210–23.

19. Behara AS, Peterson SJ, Chen Y, Butsch J, Lateef O, Komanduri S. Nutrition support in the critically ill: a physician survey. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2008;32(2):113–9.

20. Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, Kalet AL. What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. J Am Coll Nutr 2008;27(2):287–98.

21. Lee J-M, Lee JW, Jeong TS, Bang ES, Kim SH. Low Meropenem Concentration in Brain-Dead Organ Donors: A Single-Center Pharmacokinetic Study and Simulation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62(10):E00542–18.

22. McKenzie C. Antibiotic dosing in critical illness. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66(Suppl 2):ii25–31.

23. Roberts JA, Paul SK, Akova M, Bassetti M, De Waele JJ, Dimopoulos G, et al. DALI: defining antibiotic levels in intensive care unit patients: are current β-lactam antibiotic doses sufficient for critically ill patients? Clin Infect Dis 2014;58(8):1072–83.

24. Tabah A, De Waele J, Lipman J, Zahar JR, Cotta MO, Barton G, et al. The ADMIN-ICU survey: a survey on antimicrobial dosing and monitoring in ICUs. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(9):2671–7.

25. Wu CC, Tai CH, Liao WY, Wang CC, Kuo CH, Lin SW, et al. Augmented renal clearance is associated with inadequate antibiotic pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic target in Asian ICU population: a prospective observational study. Infect Drug Resist 2019;12:2531–41.

26. Hughes RG, Ortiz E. Medication errors: why they happen, and how they can be prevented. J Infus Nurs 2005;28(2 Suppl):14–24.

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 4,106 View

- 95 Download

-

Related articles in

J Acute Care Surg