Clinical Safety of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in Elderly Patients: A Comparison of Clinical Outcomes in Patients Aged 65 to 79 Years and over 80 Years

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) in elderly patients is a matter of concern because morbidity and clinical risk are higher in elderly patients; and some clinicians recommend non-surgical supportive treatments. There is limited data reported in the literature for LC in super-elderly individuals (aged ≥ 80 years). This study compared the clinical outcome for the elderly and super-elderly patients undergoing LC.

Methods

Patients who had a cholecystectomy for acute or chronic cholecystitis, and empyema of the gall bladder between January 2011 and June 2018 were analyzed retrospectively. The clinical outcomes of the super-elderly patients (≥ 80 years, Group 2) were compared with elderly patients (65-79 years, Group 1). Complications, conversion rate, postoperative hospital stays were assessed.

Results

The conversion rate was 5.5% and 8.4% in Groups 1 and 2, respectively (p = 0.749). The surgical or medical complication rates were similar in both groups. A significant difference in operation time was observed between groups (p < 0.001). Although the super-elderly patients had longer postoperative hospital stays (7.10 ± 6.98) than the elderly patients (4.60 ± 6.06), there was no significant difference with between the 2 groups (p = 1.000).

Conclusion

The clinical outcomes of the conversion rate, complications, and mortality were similar in patients aged 65 to 79 years and ≥ 80 years. Therefore, LC is deemed to be a safe and simple procedure for the super-elderly.

Introduction

The incidence of acute cholecystitis (AC) increases with age, ranging from 20% to 30% among elderly individuals, and up to 80% among institutionalized elderly patients aged > 90 years. Furthermore, > 90% AC cases are closely associated with cholelithiasis [1]. A previous study has shown that the prevalence of gallstones and AC is correlated with age [2]. The standard treatment of AC is laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) in young adults [3]. However, the safety of LC for elderly patients remains controversial owing to them having increased comorbidity risks [4]. Reduced physiologic reserve increases the risk of morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. High rates of morbidity and mortality make it challenging for surgeons to select an optimal operative management strategy [5]. Thus, many clinicians considered percutaneous biliary drainage to avoid administration of general anesthesia and surgery [6]. However, there was no clinical evidence to support this concern. Recently, perioperative care for elderly patients and LC technique has been improved, which reduces the risk associated with LC. The demand of surgery for AC has increased, and thus there is a need to evaluate the clinical safety and efficacy of LC in super-elderly patients (≥ 80 years) compared with elderly patients (≤ 65-79 years).

Materials and Methods

This study was retrospectively conducted with approval of Chosun University Hospital Ethics Review Committee (IRB no.: CHOSUN 2014-01-005). Medical records of patients who were aged > 65 and had undergone LC between January 2011 and June 2018 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were divided into 2 groups: Group 1 which comprised patients aged between 65 and 79, and Group 2 which comprised patients aged ≥ 80 years. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification system was used as a functional measure for preoperative risk assessment [7].

Age, sex, ASA score and degree of severity of the 2 groups were based on the Tokyo guidelines (TG) 2018. Conversion rate, complications and operation time were compared between these 2 groups.

1. Surgical procedure

Under general anesthesia, a pneumoperitoneum was created by following Hasson technique and was insufflated with carbon dioxide gas. With the patient in the reverse Trendelenburg position with the left side down, a 10 mm trocar was inserted through an infra-umbilical incision for placing the telescope. A 5 mm trocar was inserted in the sub-xiphoid area, and a 5 mm trocar was inserted into the right subcostal area. The cystic duct and artery were exposed and clipped using a 5 mm clip. Hemostasis was achieved with electrocautery, and the resected specimen was removed via the infra-umbilical incision site using a protective plastic bag. Routine intraoperative cholangiography was not performed. Indication for conversion to open surgery were as follows; suspicion of common bile duct (CBD) injury, unidentified cystic duct due to severe inflammation, strong adhesion resulting from a previous abdominal surgery, severe active bleeding, large stone in CBD, or suspicion of gallbladder cancer.

2. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 25.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Categorical variables were represented as mean values and ranges, and qualitative variables were described as frequency and percentage. One-way analysis of variance was used to assess differences in continuous variable between the 2 groups. The p values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

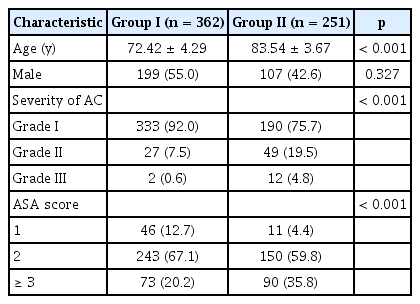

A total of 613 patients were included in this study. There gallbladderwere 362 elderly patients (Group 1) aged ≤ 65-79 years and 251 super-elderly patients (Group 2) aged ≥ 80 years. Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. There were no differences in clinical characteristics, except for ASA scores, between the 2 groups of patients. There were a significantly higher number of patients with TG-grade III severity in Group 2 compared with Group 1 (Table 1).

Comparison of characteristics between relatively younger patients. Group 1 and super-aged patients (Group 2).

A conversion from laparoscopic procedure to an open procedure was required in 20 patients (5.5%) in Group 1, and 21 patients (8.4%) in Group 2, but this difference was not significant (p = 0.749). There were no significant differences in rates of surgical complications including wound infection, hematoma in the gallbladder fossa, CBD injury, intraoperative bleeding, and bowel injury. Medical complications associated with respiratory, gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular system were not different between the 2 groups. A significant difference was observed in the operation time between groups (p < 0.001; Table 2).

A postoperative hospital stays was longer in Group 2 (7.10 ± 6.98) than Group 1 (4.60 ± 6.06), but this difference was not significant (p = 1.000; Table 2).

Discussion

The definitive treatment for AC is LC. However, LC in elderly patients has high perioperative risks. Therefore, some physicians prefer conservative treatment for AC in elderly patients, which includes the use of antibiotics or biliary drainage [8]. Several studies have shown that biliary drainage for AC can be easily and successfully performed. However, uncontrolled AC has a risk of cholangitis, septic shock, and even death. Moreover, biliary drainage is uncomfortable for patients and leads to a low quality of life [1,5,6,9].

Some studies show that LC is a feasible and safe treatment option for elderly patients [7-9]. Most of these studies have compared outcomes of this procedure in patients ≥ 65 years old with those in younger patients, and only a few studies have compared the outcomes of super-elderly and elderly patients. This current study focused on the feasibility of LC for AC in super-elderly individuals.

TG severity grading reportedly plays an important role in the outcome of LC [10] and open conversion cholecystectomy is also an important factor [11,12]. The factors affecting the outcome of LC increase postoperative complications, mortality rates, and length of hospital stay, leading to economic losses [13]. Therefore, it was determined whether these identified risk factors directly affected the clinical outcome of the 2 groups of patients.

In this current study, the males in Group 1 showed a high conversion rate, similar to findings reported by Ambe and Köhler [14]. However, this was not the case for Group 2 patients. The super-elderly patients general condition was poor compared with the elderly patients, and had more comorbidities that led to higher ASA scores. Thus, ASA scores were used for measuring the performance status, and for predicting the risk related to LC surgery, consistent with the strategy adopted in previous studies [7,15]. For evaluating the severity of AC, TG grading system was followed [10], and it was observed that super-elderly patients frequently had higher ASA scores and TG grades compared with elderly patients. However, there was no significant difference between both groups in terms of ASA score or TG grade-associated clinical outcomes.

Open conversion procedures and increased operative times are important considerations in an elderly patient because they have a lower physiologic reserve and lack the ability to withstand long surgery times [11,12]. In this current study, the conversion rate was slightly higher in Group 2 patients which resulted in prolonged operation times, leading to a higher frequency of wound infections, and prolonged hospital stays. However, this difference observed between the 2 groups was not statistically significant.

Longer hospital stays increased the economic burden on patients, which was an important concern. We observed that patients with higher ASA scores and TG gradings had longer hospital stays, consistent with the findings reported in previous studies [12,16]. In both groups, it was observed that the duration of hospitalization was longer when the ASA score was higher. The relationship between the TG level and the prolonged hospital stays was more significant in the Group 2 patients. These results suggest that the severity of the AC was more relevant to the clinical outcome than the patients’ performance status as measured by AS scores in super-elderly patients.

Bile leakage is also an important concern that could result in sepsis caused by peritonitis. When CBD injury during the laparoscopic procedure was observed or suspected, the drainage tube was retained to monitor leakage. If bile leakage was observed, an endonasal biliary drainage was performed and complete recovery was achieved. In this study, we did not observe any significant bile leakage-associated complications that could affect postoperative morbidity and mortality. No significant difference in clinical outcomes was noted between the 2 groups.

Although the super-elderly patients had longer operation time and postoperative hospital stays than the elderly patients, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups with regards to complication rates and clinical outcomes.

This study had several limitations. The data of LC surgery performed by 3 surgeons at the same medical center were collected; however, the experience of each surgeon was not considered. This may have had an influence on the operating time, conversion rate, and clinical outcomes [13]. In addition, the differences in the overall health status and the incidence of accompanying diseases which were age related were not considered. Furthermore, cases of subtotal cholecystectomy or percutaneous drainage alone, which can be easily and safely applied to manage severe inflammatory AC were excluded [17]. Moreover, the long-term outcomes of LC according to patient quality of life as well as functionality and cost-effectiveness, were not analyzed [18]. In addition, the physiologic changes resulting from initiating a pneumoperitoneum (which is essential for the laparoscopic procedure under general anesthesia), may have caused significant impairment in cardiopulmonary function, but was not analyzed [19]. Furthermore, a significant bias existed in the selection of super-elderly patients for LC because the decision for operation was made by patients and their family members based on their general physical condition. This selective difference may have influenced a better hospital course and could have affected the results for the super-elderly patents.

In conclusion, bearing in mind the limitations of this study, and contrary to the perception that LC is not suitable for AC patients aged ≥ 80 years, this study suggests that there is no significant difference in the clinical outcomes of LC surgery between elderly patients (aged 65-79 years) and super-elderly patients (aged ≥ 80 years). However, factors including comorbidities, performance status, and severity also need to be taken into consideration. Hence, avoidance of LC for AC in super-elderly patients is not mandatory if comorbidities are optimally managed and medical care is carefully provided during the perioperative course.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical Approval

Chosun University Hospital Ethics Review Committee (IRB no: CHOSUN 2014-01-005).