|

|

- Search

| J Acute Care Surg > Volume 11(2); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The outcomes of non-trauma patients requiring intra-abdominal gauze packing for the management of uncontrollable hemorrhage following surgery, and the evaluation of survival risk factors were examined.

Methods

Data from patients who underwent intra-abdominal gauze packing to control bleeding during abdominal surgery between September 2012 and March 2019 were retrospectively reviewed.

Results

A total of 28 patients were included in the study population analysis. There were 9 patients who died during hospitalization. One patient died as a result of uncontrolled bleeding. In spite of gauze packing, 2 patients who had increasing blood transfusion requirements (> 4 packs/4 hours) were found to have arterial bleeding. Univariate analysis for hospital death showed that immunocompromised status, emergency surgery, a thrombocytopenic state prior to initial surgery, and a longer duration until gauze removal had a negative association with survival outcomes. Among these factors, only time to gauze removal > 36 hours was identified as an independent risk factor for survival outcome in the multivariate analysis.

In recent decades, advances in surgical skills and surgical devices have increased the efficacy of surgery, and reduced the associated morbidity and mortality risks. However, surgeons still face many challenges such as uncontrolled hemorrhage, which remains a life-threatening scenario. The ŌĆ£bloody vicious cycle,ŌĆØ comprises coagulopathy, acidemia, and hypothermia, and this triad augments and exacerbates physiological instability [1]. It may not be feasible for surgeons to repair all identified injuries during the initial operation, and a decision may be made to complete the surgery with a 2nd procedure. However, in cases of uncontrolled bleeding, gauze packing can be useful to provide surgeons with the time needed to repair reversible physiological derangements, such as acidemia, hypothermia, and coagulopathy, which may result from prolonged surgical time and transfusion therapy.

Gauze packing can be used to control massive hemorrhage in trauma patients and in a range of severe conditions, such as liver damage, abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture, postpartum bleeding, and pelvic bleeding [2ŌĆō6]. However, there are few reports of the use of gauze packing in non-trauma patients and patients without liver injury. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the outcome of non-trauma patients who required intra-abdominal gauze packing for surgically uncontrollable hemorrhage and determine the risk factors for survival.

Data from 28 patients who underwent intrabdominal gauze packing to manage uncontrollable hemorrhage during abdominal surgery at the Asan Medical Center between September 2012 and March 2019 were evaluated. The gauze packing performed in all 28 cases was carried out by a single surgeon who used the standardized gauze packing procedure. Trauma patients and 2 patients who died during surgery or within 1 hour after surgery due to bleeding were excluded from the study population because these cases were considered as ŌĆ£death during surgery.ŌĆØ Records were reviewed for clinical characteristics (including age, sex, comorbidity, elective or emergency surgery, amount of transfusion, and number of packing gauzes used); laboratory findings were also reviewed. The primary endpoint was mortality at discharge from hospital to evaluate the survivor group and non-survivor group. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center (IRB no.:2019-1013). Due to the retrospective nature of this study informed consent was waived.

There were no definite indications for gauze packing, but a review of the cases showed that it was generally performed in the following circumstances: (1) Uncontrollable hemorrhage despite a period (> 30 minutes) of packing and manual compression, application of hemostasis materials, suture ligation, and warming; (2) Unstable vital signs despite transfusions with packed red blood cells (pRBCs); (3) Oozing hemorrhage with unstable vital signs; (4) Persistent non-arterial bleeding from the venous plexus.

Gauze packing was performed in a standard manner as follows: (1) Direct packing over the major bleeding point using dry 15 ├Ś 40 cm gauzes; (2) Additional gauzes stacked adjacent to the primary gauze packing site to enhance the tamponade effect; (3) Application of manual pressure for 10ŌĆō15 minutes; (4) Additional gauzes used if hemostasis remained unsatisfactory on the bilateral edges of the packed gauzes. The material used for packing depended on the extent of the bleeding site; if the bleeding surface was large, laparotomy pads (40 ├Ś 40 cm) and gauzes were used at the same time.

To protect the bowel, it was wrapped in a wet hand towel. In all cases, the abdomen was closed temporarily with skin and subcutaneous fat sutures with simple one-layer suturing using 1-0 polydioxanone sutures. All patients were managed in the intensive care unit (ICU) postoperatively and received ventilator support; coagulopathy and hypothermia were corrected, and hemodynamics were continuously monitored. The term ŌĆ£Next day gauze packingŌĆØ was applied to 5 patients who had not been expected to require intra-abdominal gauze packing in the initial operation but who underwent a 2nd operation to insert gauze packing because of ongoing bleeding.

The timing for gauze removal was determined according to the patientŌĆÖs condition and hemostatic status. Generally, gauze removal was considered 12 hours after the index operation and ideally no more than 48 hours later due to the increased possibility of infection. In this study, we considered gauze removal when coagulopathy and hypothermia had normalized to some extent, and a transfusion had not been required for at least 3 hours. The patients were transferred to the operating room directly from the ICU and placed in a supine position. The abdomen was prepared, draped, and the skin sutures were removed. The packed gauzes were then carefully removed from the abdominal wall and oozing sites. If the surgeon experienced any resistance, a warm saline solution was used to ease the removal of the packed gauzes without causing bleeding. After complete gauze removal, the packed sites were irrigated copiously with normal saline (3ŌĆō4 L) and checked for signs of oozing or bleeding which may have resumed. If all packed gauze was removed and there were no signs of bleeding observed, meticulous gauze counting was undertaken to ensure the total removal of all gauzes, and a radiograph of the abdomen was taken to confirm the absence of any gauze material prior to formal closure.

Categorical variables were compared using PearsonŌĆÖs Žć2 test, and continuous variables were compared using the Student t test and the Mann-Whitney test. Post-gauze packing and pre-gauze removal clinical and laboratory findings were compared using the paired t test. Binary logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate clinical and laboratory characteristics associated with patient survival. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to assess the determinant factors related to patient survival. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistical program (Version 21, IBM, Inc., Chicago, IL). In all tests, statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Data from 28 patients were included in the analysis of the study population. The etiology of abdominal hemorrhage is listed in Table 1. The clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2. There were no differences in age, sex, number of transfused blood components during surgery, or number of gauzes used between the survivor and non-survivor groups. Furthermore, there were no differences in laboratory findings (platelet count, C-reactive protein, and lactic acid) just prior to gauze removal between the 2 groups. However, the non-survivor group contained more immunocompromised patients (transplant patients, and patients with cytopenia as a result of chemotherapy), thrombocytopenia patients, and those patients requiring a longer duration to gauze removal.

The clinical and laboratory findings following gauze packing and prior to gauze removal are summarized in Table 3. The mean surgical time required for gauze removal was 105 ┬▒ 71 minutes. Nineteen (70.4%) of 27 patients only underwent gauze removal. Eight (29.6%) of 27 patients underwent additional tumor resection or bowel resection and anastomosis during gauze removal surgery.

A total of 9 patients died during hospitalization (median survival, 38 days; range, 0ŌĆō138 days), with only 1 patient dying as a result of uncontrolled bleeding. The cause of death in the remaining patients was uncontrolled infection (n = 6), bowel ischemia (n = 1), and disease recurrence (n = 1). Three of the total deaths were recorded in the 1st month after gauze packing.

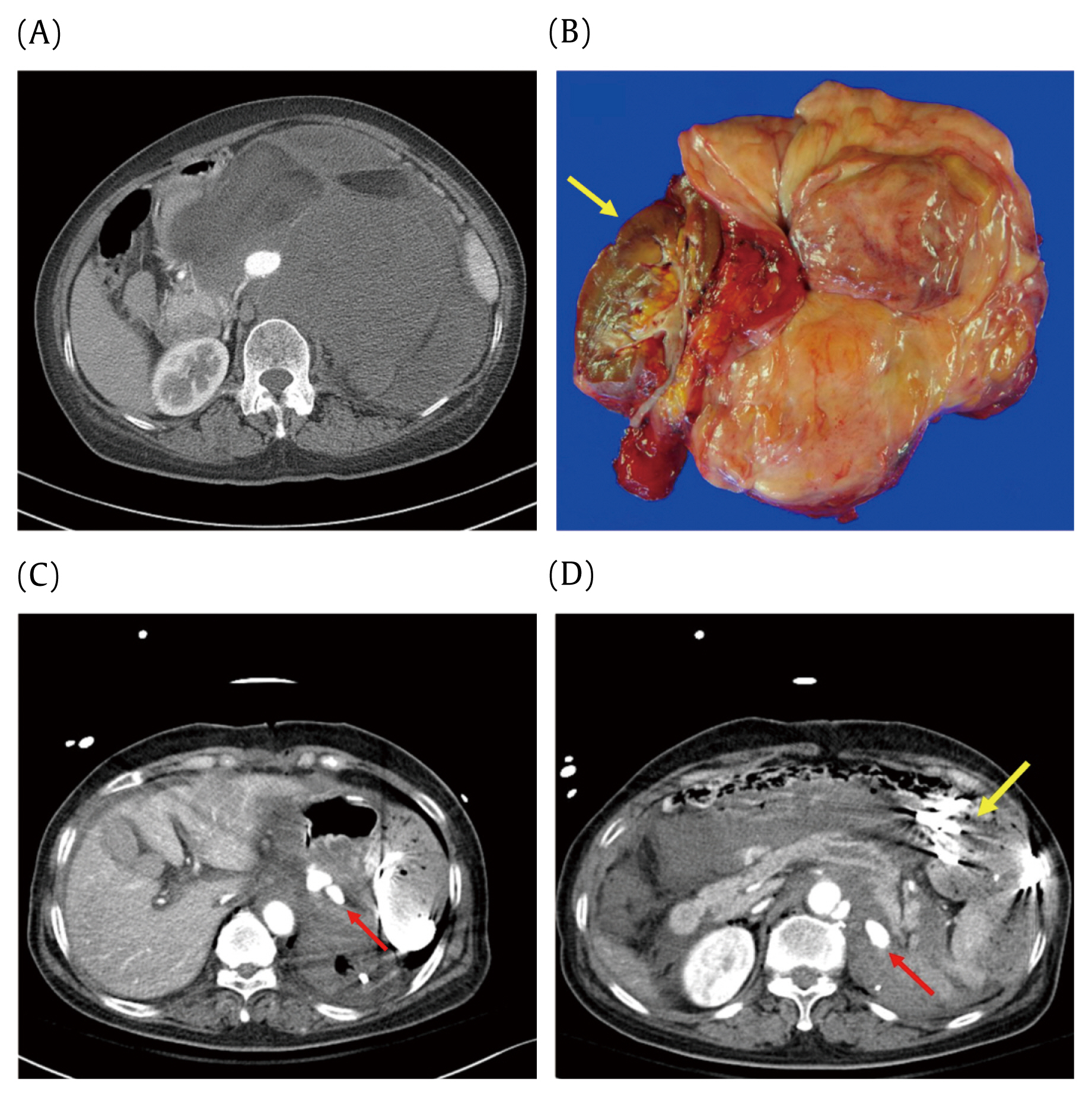

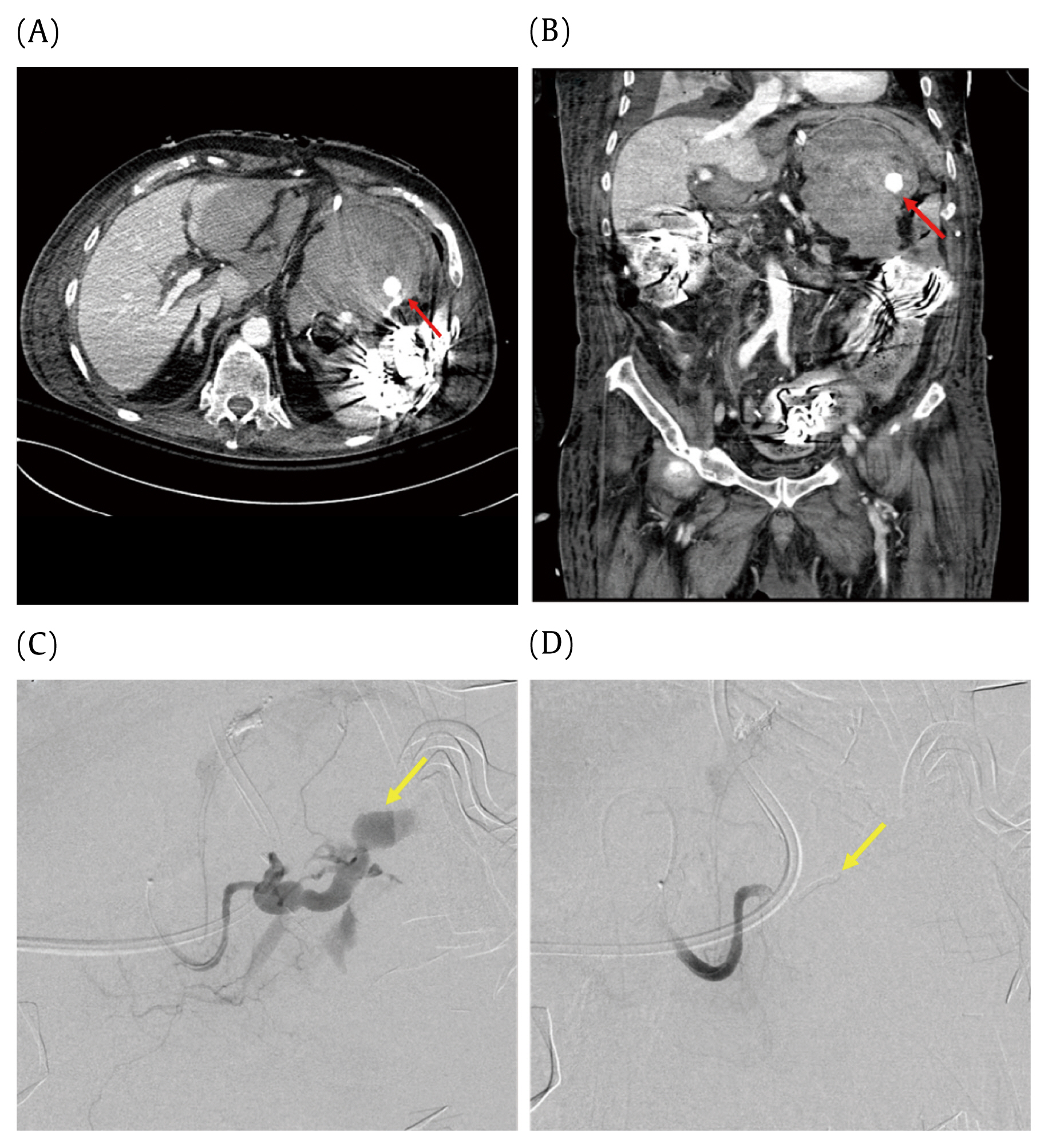

In spite of gauze packing, 2 patients who had consistently increased blood transfusion requirements (> 4 packs/4 hours) were found to have arterial bleeding. The 1st patient was a 68-year-old female with a 30 ├Ś 25 cm mass in the left side her abdomen. In the 1st operation, the patient underwent excision of the mass within the left kidney and the patch aortoplasty technique was applied. Despite transfusion with 6 units of pRBCs and 8 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) over 4 hours, the patientŌĆÖs vital signs remained unstable. Therefore, gauze packing was inserted during a 2nd operation. Following surgery, despite previously receiving 8 units of pRBCs and 4 units of FFP, this patient still required transfusions. An enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan showed extravasation of contrast from the splenic artery branch, and a 3rd operation was performed to control the bleeding with suture ligation and repeat gauze packing (Figure 1). After 36 hours, the bleeding had stopped, and the gauze was removed. The patient remains alive to date. The 2nd patient was an 86-year-old male with anastomosis failure and ischemic enterocolitis. The patient underwent jejunal segmental resection with jejunostomy because of anastomosis failure and left hemicolectomy with splenectomy due to ischemic colitis and spleen injury. After the 1st operation, the patient received 17 units of pRBCs and 20 units of FFP over 7 hours; with the consent of the patientŌĆÖs family, gauze packing was performed in the ICU. However, despite this, 14 units of pRBCs and 10 units of FFP were required over 16 hours. Enhanced abdominopelvic CT scan showed extravasation of contrast from the splenic artery branch (Figure 2). Due to the patientŌĆÖs poor physical condition, bleeding had to be controlled by embolization, which was successful. However, the patient died 45 days later as a result of an uncontrolled infection.

In the univariate analysis, immunocompromised patients, emergency surgery, a thrombocytopenic state before the initial surgery, and a longer duration until gauze removal were determined to have an impact on survival outcome. Among these factors, only a duration of > 36 hours to gauze removal was determined to be an independent risk factor for survival in the multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Compression has long been used as a simple and effective method of hemostasis. Therefore, gauze packing is commonly used in a range of cases from simple epistaxis and wound bleeding to massive bleeding as a result of trauma. Gauze packing of the abdomen has been recognized as a useful intervention in the management of trauma patients with massive hemorrhage [7ŌĆō9]. The pathogenesis of the ŌĆ£bloody vicious cycleŌĆØ is complex and results from massive transfusion, persistent cellular shock and clotting factor deficiencies, promoting and exacerbating hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy [1]. Sharp et al identified that acidosis (pH Ōēż 7.18), hypothermia (temperature Ōēż 33┬░C), coagulopathy (prothrombin time Ōēź 16 seconds, thromboplastin time Ōēź 50 seconds), and massive transfusion (Ōēź 10 units) were risk factors for poor outcome [6]. The major goal of intra-abdominal gauze packing is to break the ŌĆ£bloody vicious cycleŌĆØ and to restore normal physiological parameters. The use of gauze packing to halt severe hemorrhage during abdominal surgery is also thought to be plausible in non-trauma patients where it can be a life-saving modality.

Intra-abdominal packing, particularly peri-hepatic gauze packing, is an accepted technique for the control of hemorrhage following severe hepatic trauma [10,11]. A recent study reported that this approach was highly effective in achieving hemostasis during liver transplantation surgery [3]. Gauze packing has also been shown to be highly effective for the management of hemorrhage from large retroperitoneal veins [12,13]. In the current study, gauze packing was a very useful method of controlling paravertebral venous plexus bleeding (Figure 3) and retroperitoneal vein bleeding [12]. In obstetrics, intrauterine gauze or abdominopelvic gauze packing is a life-saving method for controlling postpartum bleeding [13ŌĆō15]. Hemostasis through gauze packing has recently been reported in patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair or severe thoracic trauma [2,16,17].

The decision to perform gauze packing is a difficult one, and the timing is controversial. The indications for damage control surgery for abdominal trauma are generally hemorrhagic shock due to intra-abdominal bleeding with acidosis, coagulopathy, and hypothermia (the lethal triad), or a condition worsening progressively toward the lethal triad of conditions [12,17]. However, there are no specific guidelines for gauze packing in non-trauma patients. Furthermore, unlike trauma patients, gauze packing in non-trauma patients is characterized by less severe hypothermia and acidosis, because gauze packing is performed before hypothermia or acidosis becomes severe. In the current study, hemostasis was attempted in patients with no preoperative problems rather than gauze packing after Ōēź 10 pRBCs units had been transfused. However, in the case of thrombocytopenia and/or preoperative prolongation of prothrombin time, if oozing bleeding was observed, gauze packing was considered rather than hemostasis. It is important to make appropriate and quick decisions on whether to perform gauze packing based on the patientŌĆÖs condition.

The packing technique involves the use of dry gauzes placed directly over the injury by exerting pressure and compressing bleeding points against bone or fascia in cases involving the pelvis, paravertebral site, or retroperitoneal venous bleeding. In the case of diffuse oozing bleeding or bleeding over a large area, dry gauzes are placed over the dissected area with the abdomen closed under tension to provide tamponade. However, the risk of abdominal compartment syndrome must be considered if too much pressure is applied. The patient population of this study were non-trauma patients, therefore severe bowel edema rarely occurred. So abdominal compartment syndrome rarely occurred. If bleeding persists despite adequate packing, arterial bleeding or large vessel injury should be suspected. In the present study, 2 patients had persistent bleeding after packing, and an enhanced CT scan revealed evidence of arterial bleeding. If the patientŌĆÖs vital signs are maintained, it may be more helpful to consider a 2nd operation after an enhanced CT scan.

When the patientŌĆÖs vital signs are hemodynamically stable, and hypothermia and coagulopathy have been corrected, then, gauze removal surgery should be considered. Prior to removing the gauze, it is essential to moisten the gauze packing area to avoid re-bleeding. Gauze removal has been recommended within 12ŌĆō36 hours following the initial surgery [7,18]. One study has shown that removing perihepatic packs 36ŌĆō72 hours after gauze packing reduced the risk of re-bleeding without increasing the risk of liver-related complications in hepatic injury patients [10]. Abikhaled et al [19] reported that higher rates of abscess formation and mortality were observed if packed gauzes were left in place for > 72 hours. We noted 2 cases of which pigtail catheter insertion was required for drainage of an intra-abdominal abscess. Nevertheless, the pigtail catheter insertion was performed 2ŌĆō3 weeks after gauze removal which makes it difficult to infer that the abscess was due to gauze packing. Thus, there was no notable abscess formation directly caused from gauze packing in our study.

In the current study, 20 of 27 patients (74%) underwent successful gauze removal within 36 hours of the index operation without re-bleeding. Six of the 7 patients (85.7%) who underwent gauze packing removal after 36 hours died, which was determined to be a significant risk factor in the multivariate analysis. This may be related to the poor general condition of the patients before the index operation, which made the correction of coagulopathy challenging, and delayed the timing of gauze removal. We can presume that the patientsŌĆÖ poor general conditions also prevented their recovery.

In conclusion, gauze packing is a very effective approach to the management of uncontrolled hemorrhage in non-trauma patients. In cases of persistent bleeding after gauze packing, arterial bleeding should be suspected. A delay in gauze removal of > 36 hours can lead to poor survival outcomes.

Figure┬Ā1

A 68-year-old female patient. (A) Preoperative computed tomography (CT) findings showing a large mass encasing the aorta and occupying the whole left abdomen. (B) Well-differentiated liposarcoma 29 ├Ś 23 ├Ś 13 cm in size. The yellow arrow indicates the left kidney. (C) and (D) Postoperative enhanced CT performed after the initial operation demonstrates active extravasation. The red arrow indicates extravasation of contrast media, and the yellow arrow indicates the packed gauzes.

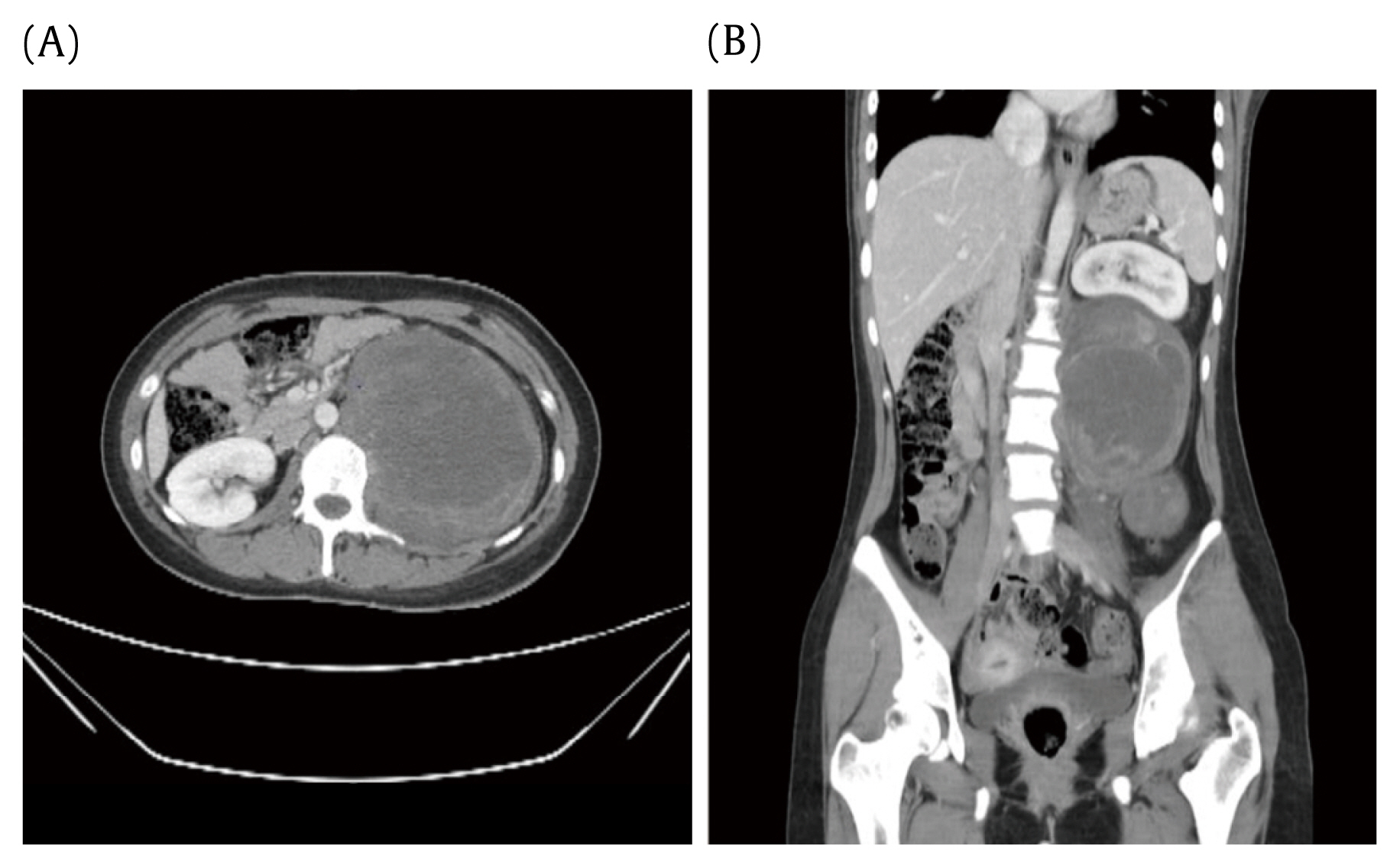

Figure┬Ā2

An 86-year-old male patient who underwent left hemicolectomy, small bowel resection, and splenectomy because of bowel infarction and perforation and iatrogenic spleen injury. (A) Enhanced abdominopelvic CT (axial view) after gauze packing. The red arrow indicates extravasation of contrast media. (B) Enhanced abdominopelvic CT (coronal view) after gauze packing. The red arrow indicates extravasation of contrast media. (C) Active extravasation was seen at the splenic artery (yellow arrow). (D) Splenic artery embolized with coils (yellow arrow) and gelfoam.

Figure┬Ā3

22-year-old female patient who underwent retroperitoneal tumor excision; 15 units of pRBCs were transfused during the operation, and 20 gauzes were packed to control paravertebral venous plexus bleeding. (A) Enhanced abdominopelvic CT (axial view). (B) Enhanced abdominopelvic CT (coronal view) showing the mass firmly attached to the left side of the vertebra.

Table┬Ā1

Etiology of disease/condition and survival in the study population of 28 patients treated with intra-abdominal gauze packing.

Table┬Ā2

Clinical and laboratory data in survivors and non-survivors prior to discharge.

| Variables | Survivors (n = 19) | Non-survivors (n = 9) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 54 ┬▒ 14 | 57 ┬▒ 21 | 0.681 |

|

|

|||

| Sex | 0.197 | ||

| ŌĆāFemale | 10 (52.6) | 7 (77.8) | |

| ŌĆāMale | 9 (47.4) | 2 (22.2) | |

|

|

|||

| Immunocompromised* | 1 (5.3) | 5 (55.6) | 0.002 |

|

|

|||

| Type of surgery | 0.001 | ||

| ŌĆāElective | 15 (78.9) | 1 (11.1) | |

| ŌĆāEmergency | 4 (21.1) | 8 (88.9) | |

|

|

|||

| Next day gauze packing | 2 (10.5) | 3 (33.3) | 0.141 |

|

|

|||

| Preoperative platelets (├Ś103/╬╝L) | 219 ┬▒ 123 | 102 ┬▒ 134 | 0.012 |

|

|

|||

| No. of units transfused (intraoperative range) | |||

| ŌĆāpRBC | 17.5 ┬▒ 12.4 (2ŌĆō60) | 20.5 ┬▒ 11.1 (5ŌĆō34) | 0.541 |

| ŌĆāFFP | 9.0 ┬▒ 9.8 (0ŌĆō43) | 16.2 ┬▒ 12.4 (0ŌĆō34) | 0.117 |

| ŌĆāPlatelet concentrate | 3.8 ┬▒ 5.7 (0ŌĆō20) | 18.7 ┬▒ 10.3 (0ŌĆō32) | 0.001 |

| ŌĆāCryoprecipitate | 2.4 ┬▒ 6.3 (0ŌĆō20) | 0.7 ┬▒ 2.0 (0ŌĆō9) | 0.847 |

|

|

|||

| No. of packing gauzes | 49.4 ┬▒ 24.5 (15ŌĆō105) | 40.0 ┬▒ 22.1 (7ŌĆō69) | 0.468 |

|

|

|||

| Time to gauze removal (h) | 23.8 ┬▒ 6.9 | 43.1 ┬▒ 15.9 | < 0.001 |

|

|

|||

| Values prior to gauze removal | |||

| ŌĆāPlatelets, ├Ś103/╬╝L | 101 ┬▒ 30 | 82 ┬▒ 77 | 0.119 |

| ŌĆāCRP (mg/dL) | 8.4 ┬▒ 6.4 | 8.7 ┬▒ 7.3 | 0.856 |

| ŌĆāLactic acid (mmol/L) | 2.07 ┬▒ 0.94 | 5.20 ┬▒ 4.50 | 0.163 |

Table┬Ā3

Comparison of clinical and laboratory findings following gauze packing and prior to gauze removal.

Table┬Ā4

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with survival in intra-abdominal gauze packed patients.

| Parameter | No. patients | No. deaths (%) | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |||

| Immunocompromised | 0.011 | 0.302 | ||||

| ŌĆāNo | 22 | 4 (18.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ŌĆāYes | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 22.5 (2.031ŌĆō249.239) | 7.604 (0.161ŌĆō358.833) | ||

|

|

||||||

| Type of surgery | 0.005 | 0.356 | ||||

| ŌĆāElective | 16 | 1 (6.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ŌĆāEmergency | 12 | 8 (66.7) | 30.000 (2.852ŌĆō315.612) | 6.601 (0.120ŌĆō365.345) | ||

|

|

||||||

| Preoperative platelet count | 0.031 | 0.847 | ||||

| ŌĆāNormal | 15 | 2 (13.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ŌĆāThrombocytopenia* | 13 | 7 (53.8) | 7.583 (1.198ŌĆō48.004) | 0.670 (0.011ŌĆō39.647) | ||

|

|

||||||

| Time to gauze removal (h) | 0.002 | 0.025 | ||||

| ŌĆā< 36 | 20 | 2 (10.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ŌĆāŌēź 36 | 7 | 6 (85.7) | 54.000 (4.124ŌĆō707.058) | 32.478 (1.564ŌĆō674.293) | ||

References

1. Moore EE, Thomas G. Orr memorial lecture. Staged laparotomy for the hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy syndrome. Am J Surg 1996;172(5):405ŌĆō10.

2. Adam DJ, Fitridge RA, Raptis S. Intra-abdominal packing for uncontrollable haemorrhage during ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2005;30(5):516ŌĆō9.

3. Patrono D, Romagnoli R, Tandoi F, Maroso F, Bertolotti G, Berchialla P, et al. Peri-hepatic gauze packing for the control of haemorrhage during liver transplantation: A retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis 2016;48(4):414ŌĆō22.

4. Awonuga AO, Merhi ZO, Khulpateea N. Abdominal packing for intractable obstetrical and gynecologic hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006;93(2):160ŌĆō3.

5. Ge J, Liao H, Duan L, Wei Q, Zeng W. Uterine packing during cesarean section in the management of intractable hemorrhage in central placenta previa. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;285(2):285ŌĆō9.

6. Sharp KW, Locicero RJ. Abdominal packing for surgically uncontrollable hemorrhage. Ann Surg 1992;215(5):467ŌĆō74. discussion 474ŌĆō5.

7. Morris JA Jr, Eddy VA, Blinman TA, Rutherford EJ, Sharp KW. The staged celiotomy for trauma. issues in unpacking and reconstruction. Ann Surg 1993;217(5):576ŌĆō84. discussion 584ŌĆō6.

8. David Richardson J, Franklin GA, Lukan JK, Carrillo EH, Spain DA, Miller FB, et al. Evolution in the management of hepatic trauma: A 25-year perspective. Ann Surg 2000;232(3):324ŌĆō30.

9. Kapan M, Onder A, Oguz A, Taskesen F, Aliosmanoglu I, Gul M, et al. The effective risk factors on mortality in patients undergoing damage control surgery. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2013;17(12):1681ŌĆō7.

10. Caruso DM, Battistella FD, Owings JT, Lee SL, Samaco RC. Perihepatic packing of major liver injuries: Complications and mortality. Arch Surg 1999;134(9):958ŌĆō62. discussion 962ŌĆō3.

11. Kozar RA, Feliciano DV, Moore EE, Moore FA, Cocanour CS, West MA, et al. Western Trauma Association/critical decisions in trauma: Operative management of adult blunt hepatic trauma. J Trauma 2011;71(1):1ŌĆō5.

12. Zama N, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Lavery IC, Weakley FL, Church JM. Efficacy of pelvic packing in maintaining hemostasis after rectal excision for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1988;31(12):923ŌĆō8.

13. Dryjski ML, Litwinski RA, Karakousis CP. Internal packing in the control of hemorrhage from large retroperitoneal veins. Am J Surg 2005;189(2):208ŌĆō10.

14. Touhami O, Bouzid A, Ben Marzouk S, Kehila M, Channoufi MB, El Magherbi H. Pelvic packing for intractable obstetric hemorrhage after emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2018;73(2):110ŌĆō5.

15. Yoong W, Lavina A, Ali A, Sivashanmugarajan V, Govind A, McMonagle M. Abdomino-pelvic packing revisited: An often forgotten technique for managing intractable venous obstetric haemorrhage. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019;59(2):201ŌĆō7.

16. Vargo DJ, Battistella FD. Abbreviated thoracotomy and temporary chest closure: An application of damage control after thoracic trauma. Arch Surg 2001;136(1):21ŌĆō4.

17. Moriwaki Y, Toyoda H, Harunari N, Iwashita M, Kosuge T, Arata S, et al. Gauze packing as damage control for uncontrollable haemorrhage in severe thoracic trauma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013;95(1):20ŌĆō5.