|

|

- Search

| J Acute Care Surg > Volume 13(1); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Chylothorax is mostly iatrogenic, with blunt chest trauma being a rare cause. Treatment depends on the volume of drainage. Specifically, conservative treatment, such as total parenteral nutrition and pleural drainage, is performed in cases of low daily output (< 500 mL/day). Patients with persistent chylothorax despite medical treatment or with high daily output (> 1–1.5 L/day) are candidates for surgical or radiological intervention. We present a case of delayed-onset chylothorax after blunt trauma caused by thoracic spine fractures, in which persistent chylothorax was successfully managed with repeated lymphangiography with lipiodol when other treatment modalities failed. The case is peculiar in that the chylothorax occurred 40 days after the initial traumatic event and was treated with lipiodol injection, despite maintaining moderate to high daily output.

Chylothorax refers to the accumulation of chylous effusion in the pleural cavity. It is diagnosed by the presence of milky white fluid with high triglyceride concentrations (> 110 mg/dL) [1]. Chylothorax is associated with significant morbidity and mortality if left untreated [2,3]. Without adequate drainage, increasing thoracic pressure may cause cardiopulmonary compromise, and severe nutritional derangements may arise from continuous chylous leaks [2,3]. Chylothorax is mostly iatrogenic, with blunt trauma being a rare cause [1]. We present a rare case of delayed-onset chylothorax caused by blunt chest trauma with persistent high daily output. The patient was unresponsive to conservative treatment and multiple attempts at thoracic duct embolization (TDE) failed due to technical difficulties. He was successfully managed with repeated lymphangiography with lipiodol.

A 45-year-old male with no past medical history presented to the Emergency Trauma Department after being crushed by a 2-ton metal frame which landed on his back. The patient was hemodynamically unstable upon arrival, with a blood pressure of 72/50 mmHg and a heart rate of 101 beats/minute. Evaluation following resuscitation revealed numerous injuries, including a grade 3 liver laceration, bilateral hemopneumothorax, unstable pelvic fractures, and multiple spinal (T10–11, L1, L4, and L5) and lower-extremity fractures. The patient’s hemodynamic status was stabilized after massive transfusion (23, 17, and 10 units of red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and concentrated platelets, respectively), bilateral closed thoracostomies, and emergent surgical fixations for the bony fractures. The bilateral chest tubes were removed on the 16th hospital day (HD) without immediate complications. By the 17th HD, the patient was stable enough to be transferred to the general ward.

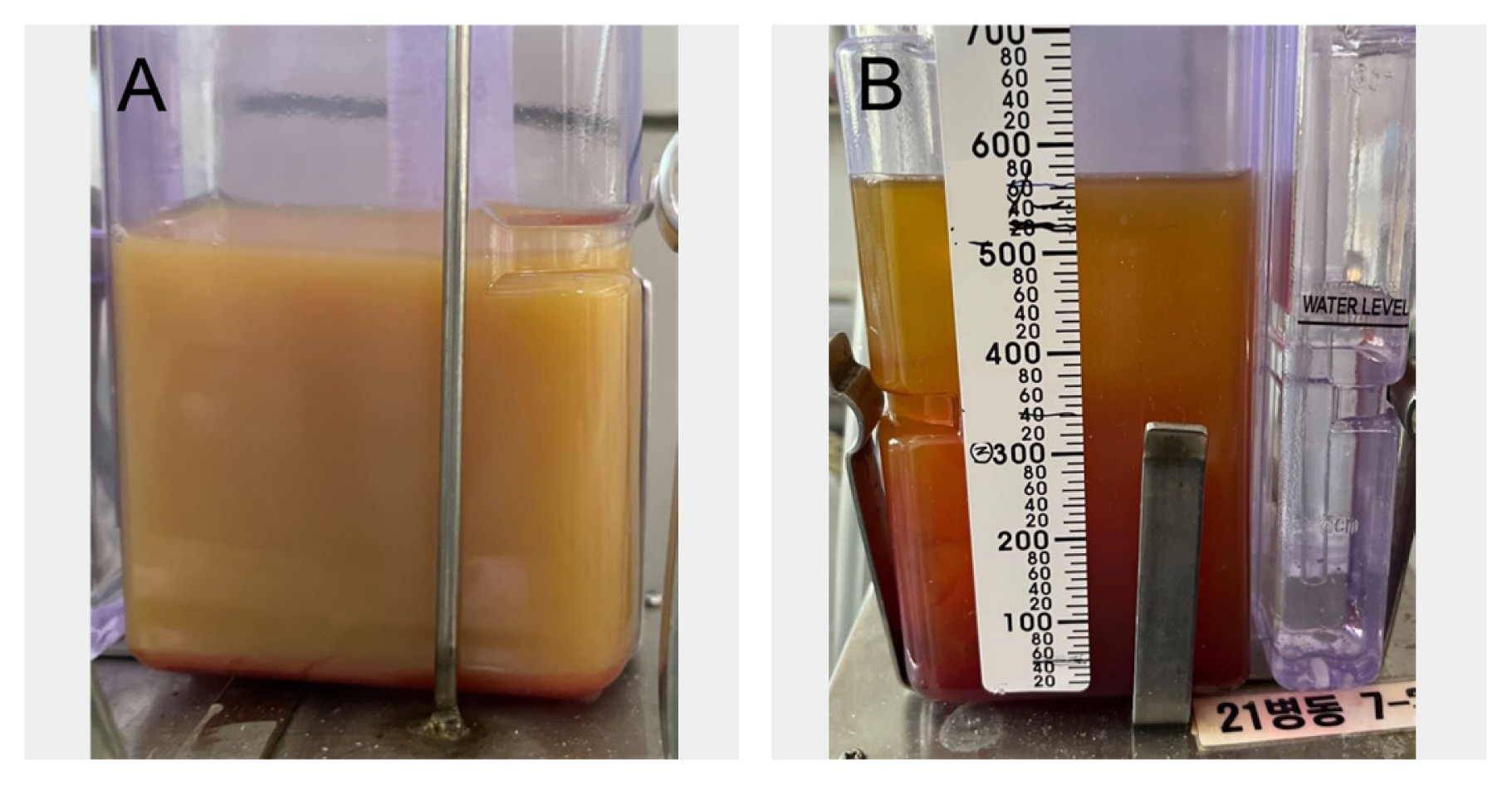

On the 40th HD, the patient expressed mild discomfort in the chest on the left side. Chest radiography showed left-sided pleural effusion (Figure 1A). In total, 1,190 mL of turbid yellow chyle, which had a triglyceride level of 407 mg/dL, was drained through a percutaneous drainage tube (Figure 2A). The patient was placed on commercially available total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and fasting for 10 days. However, despite conservative treatment, chylothorax did not improve, and the volume being drained remained high. Radiological intervention was the next therapeutic approach applied.

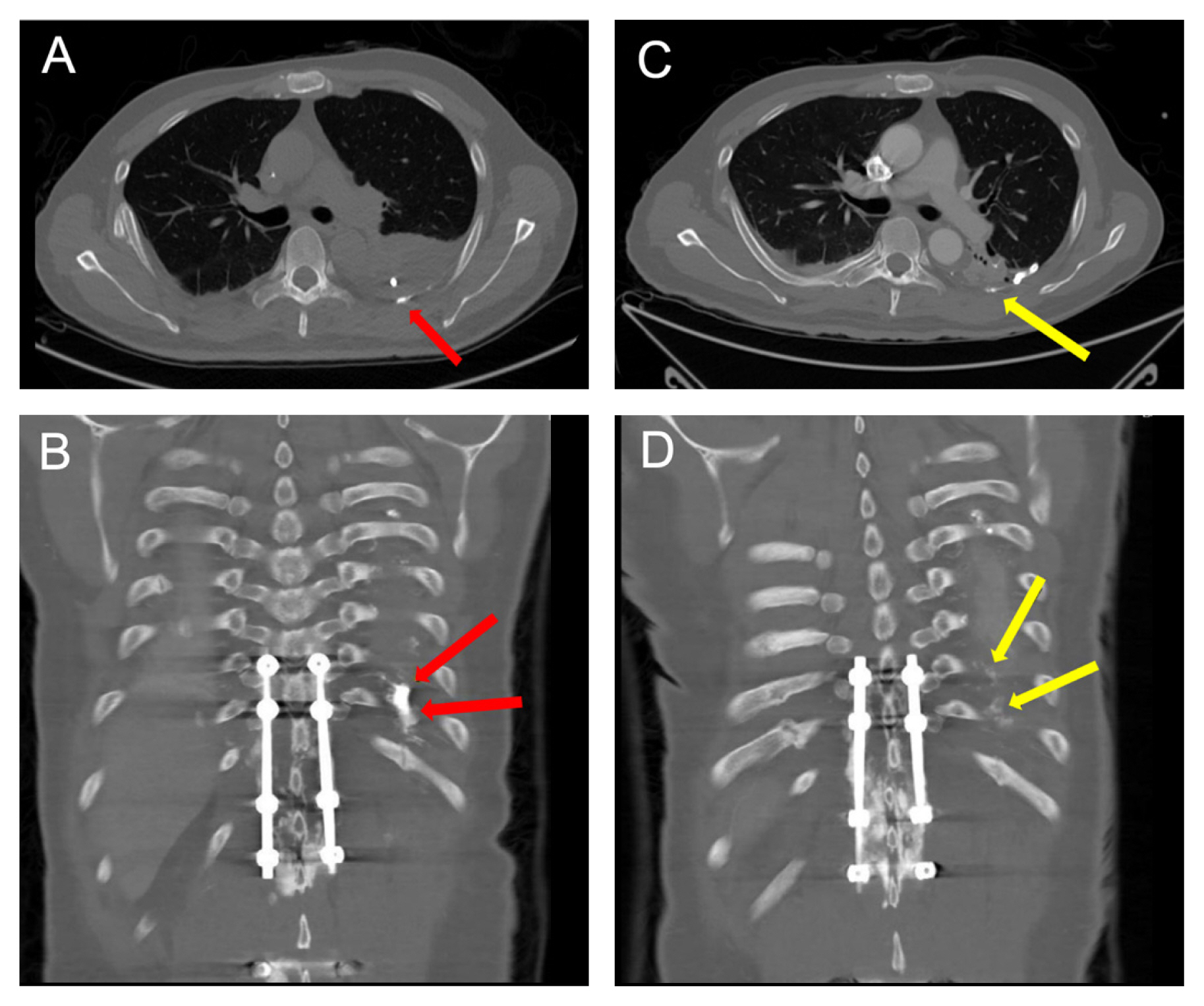

Conventional intranodal lymphangiography was performed using the right inguinal lymph nodal approach, and 9.5 mL of lipiodol was injected (Figure 3A). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) taken after 5 hours showed lipiodol leakage in the left hemithorax near to the injured T10–11 level, indicating a persistent chyle leak (Figures 4A and 4B). Multiple TDE attempts were performed. Firstly, a percutaneous approach to paraaortic lymph nodes through the back was attempted on the 61st HD, but was unsuccessful. Secondly, a retrograde approach through the left subclavian vein was performed on the 64th HD, but thoracic duct cannulation was not achieved. Chylothorax remained unresolved throughout this period, with persistent daily outputs above 200 mL.

A 2nd intranodal lymphangiography with lipiodol was performed on the 68th HD. The lymphatic system was accessed via the left inguinal lymph node, and 10 mL of lipiodol was injected (Figure 3B). Lymphangiography showed a suspicious leak at the T11 level, and transabdominal approach for TDE was attempted, but failed. Although all three TDE attempts were technically unsuccessful, CTA taken one day after the 2nd lipiodol injection showed decreased lipiodol leak (Figures 4C and 4D). On subsequent days, the volume of pleural fluid drainage decreased, and the color of the leak changed from milky yellow to clear yellow (Figure 2B). Pleural triglyceride levels decreased from 407 mg/dL on the 40th HD to 94 mg/dL by the 79th HD, indicating that lipiodol injection alone showed a therapeutic effect (Figure 5). The drainage tube was removed on the 79th HD, 39 days after its insertion. Chest radiography showed no increase of pleural effusion, and the patient did not demonstrate any symptoms or aggravation (Figure 1B).

Chylothorax can be spontaneous or iatrogenic, with the latter accounting for most cases. About 0.4–2% of chylothorax cases occur during operations for esophageal disorders [1]. Penetrating chest trauma, such as gunshot or stab wounds, is another prevalent cause of chylothorax. In contrast, chylothorax caused by blunt trauma is a rare entity [1]. It is reportedly caused by abrupt vertebral column hyperextension leading to thoracic duct rupture, or by penetrating ductal injuries due to fractured vertebral pieces [1]. The latency period between initial blunt trauma and clinical manifestation of chylothorax ranges from a few minutes to as long as 20 years [1]. In most cases, chylothorax appeared within 2–7 days from the initial trauma [1]. Our patient showed a delayed case of chylothorax which manifested as mild chest discomfort 40 days after the initial traumatic event. However, there is also the possibility that chylothorax occurred as a complication of surgical fixation to the thoracic spine, because chylothorax may appear following thoracic, cardiovascular, or spinal surgeries [4,5]. The definite causality cannot be determined for our patient who underwent spinal fixation on the same day as the traumatic injury.

General guidelines for the management of chylothorax have been established, but a definite consensus on managing chylothorax after blunt trauma has not yet been clearly defined. Management depends on the volume of daily drainage. In the case of low-output (< 500 mL/day) chylothorax, conservative treatment, such as no-fat diet or starvation with TPN and supplementary octreotide, is sufficient [1,3]. Pleural drainage is then performed to remove the collecting fluid and expand the lungs, which may promote sealing of the injured thoracic duct [1]. High-output chylothorax (> 1–1.5 L/day) should be managed with surgical or radiological intervention, for they are less likely to respond to conservative management [3]. Patients who do not respond to prolonged conservative treatment may also be a candidate to more invasive treatments [3]. However, there is no consensus as to the length of time that conservative therapy should be maintained [3,6]. If chylous drainage persists for ≥ 5 days with daily outputs > 300 mL or over 2 weeks with daily outputs of 100–200 mL despite conservative management, conversion to other treatments is highly recommended [7]. Patients developing malnutrition or metabolic complications due to loss of chyle should also be candidates for changing treatment modalities [7].

Surgical treatment of chylothorax includes mass ligation at the diaphragmatic level or selective ligation of the thoracic duct at the leakage site [1]. Success rates of thoracic duct ligation are as low as 67% [8]. Recently, lymphangiography and TDE have replaced surgical ligation as the treatment of choice [9]. Surgery is preferred if either percutaneous treatment is not available or has failed [6]. The patient refused to undergo anymore operations, therefore, we proceeded with lymphangiography and TDE after 10 days of watchful waiting. TDE holds an advantage over surgical procedures in that the surgeon can visually assess the anatomy of the lymphatic system and leakage site [8]. However, clinical success is primarily dependent on technical success of lymphatic cannulation, and some approaches require a high level of expertise which is achieved following a long learning curve [7,10]. Technical success rates reported for TDE fall within 47–90% [7]. Retrograde TDE may be performed via transvenous catheterization or transcervical puncture of the thoracic duct. It may also be achieved transabdominally under fluoroscopy following lymphangiography, after which embolization is typically performed with coils and cyanoacrylate glue [8,9].

Lipiodol is an iodinated poppy seed oil used as a contrast for lymphangiography [7]. Lymphangiography using lipiodol has some therapeutic properties by inducing selective blockage of lymph ducts, and causes sterile inflammatory reactions which lead to scarring [7]. Single or repetitive lymphangiography alone have clinical success rates of 51–100% [7]. In another meta-analysis it was reported that lymphangiography had a technical and clinical success rate of 94.2% in patients with chylothorax [11]. Although the clinical success of lymphangiography is largely dependent on drainage volume, with lower success rates in high-output fistulas [7], our patient, who maintained a high chylous output throughout the course of 39 days, showed therapeutic effect with intranodal lipiodol injection alone. Lamine et al [12] reported a case of postoperative chylothorax which was managed with repeated lymphangiography with lipiodol. The case was similar to our patient in that conservative management was not successful and catheterization required for TDE was technically unachievable. However, our patient maintained a much higher daily output, exceeding 1,000 mL per day. Yamamoto et al [13] reported a case of chylothorax after hepatectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma where the patient showed high-output fistula with over 1,000 mL/day, and pleural effusion which was resolved 10 days after lymphangiography with lipiodol alone. These examples show that lipiodol injection alone can be sufficient in managing even high-output chylothorax.

Delayed chylothorax may occur after blunt trauma to the chest with thoracic spine fractures. Management of chylothorax depends largely on the volume of daily output, with medical conservative treatment for low-output fistulas and surgical or radiological management for high-output fistulas. Noninvasive treatment, such as lymphangiography with lipiodol alone, can be used to successfully manage high-output chylothorax caused by blunt trauma.

Notes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: YH. Methodology: GK and YH. Formal investigation: GK. Writing original draft: GK. Writing - review and editing: GK, DN, BMK and YH.

Figure 1

Anteroposterior chest radiographs (A) 40th hospital day showing a left-sided pleural effusion; and (B) 84th hospital day showing no relapse of chylothorax.

Figure 2

Pleural fluid drainage (A) milky yellow fluid with elevated triglyceride level was drained after inserting the external drain tube; and (B) serous fluid drained after the 2nd lymphangiography with lipiodol.

Figure 3

Conventional intranodal lymphangiography (A) 1st lymphangiography via the right inguinal lymph node with lipiodol injection; and (B) 2nd lymphangiography via the left inguinal lymph node with lipiodol injection.

Figure 4

Computed tomography angiography (A) axial; and (B) coronal views taken 5 hours after the lymphangiography [lipiodol leak (arrows)] is seen in the left hemithorax; (C) axial; and (D) coronal views taken after the 2nd lymphangiography. The lipiodol leak is much decreased as seen in the left hemithorax (arrows).

References

1. Kakamad FH, Salih RQM, Mohammed SH, HamaSaeed AG, Mohammed DA, Jwamer VI, et al. Chylothorax caused by blunt chest trauma: a review of literature. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;36(6):619–24.

2. Gaba RC, Owens CA, Bui JT, Carrillo TC, Knuttinen MG. Chylous ascites: a rare complication of thoracic duct embolization for chylothorax. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011;34(Suppl 2):S245–9.

3. Bacon BT, Mashas W. Chylothorax caused by blunt trauma: case review and management proposal. Trauma Case Rep 2020;28:100308.

5. Weening AA, Schurink B, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R, Bleys R, Kruyt MC. Chyluria and chylothorax after posterior selective fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur Spine J 2018;27(9):2088–92.

6. Schild HH, Strassburg CP, Welz A, Kalff J. Treatment options in patients with chylothorax. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2013;110(48):819–26.

7. Pieper CC, Hur S, Sommer CM, Nadolski G, Maleux G, Kim J, et al. Back to the future: lipiodol in lymphography-from diagnostics to theranostics. Invest Radiol 2019;54(9):600–15.

8. Nadolski GJ, Itkin M. Lymphangiography and thoracic duct embolization following unsuccessful thoracic duct ligation: imaging findings and outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;156(2):838–43.

9. Drabkin M, Maybody M, Solomon N, Kishore S, Santos E. Combined antegrade and retrograde thoracic duct embolization for complete transection of the thoracic duct. Radiol Case Rep 2020;15(7):929–32.

10. Kalia S, Narkhede A, Yadav AK, Bhalla AK, Gupta A. Retrograde transvenous selective lymphatic duct embolization in post donor nephrectomy chylous ascites. CEN Case Rep 2022;11(1):1–5.

11. Kim PH, Tsauo J, Shin JH. Lymphatic interventions for chylothorax: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018;29(2):194–202e4.