|

|

- Search

| J Acute Care Surg > Volume 13(3); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The consequences of severe traumatic injury extend beyond hospital admission and have the potential for long-term functional, psychological, and economic sequalae. This study investigated patient outcomes 6 months following major trauma.

Methods

Using the National Trauma Registry, database of patients who were admitted between 2016ŌĆō18 in a tertiary trauma hospital for major trauma [Injury Severity Score (ISS) Ōēź 16] a review was performed on 6-month outcomes [including functional outcomes, self-reported state of health and outcome scores (EuroQol-5 Dimension score and Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended)].

Result

There were 637 patients who were treated for major trauma (ISS Ōēź 16); the median age was 64 years (range 16ŌĆō100) and 435 (68.3%) patients were male. The most common injury mechanisms included falling from height (56.5%) and motor vehicle accident (27.0%). The median ISS was 24 (range 16ŌĆō75). After 6 months, 87.6% of responders were living at home, 25.0% were back to work, and 55.1% were ambulating independently. The median self-rated state of health was 73 at baseline and 64 at 6 months. Age and length of stay were independent predictors of return to ambulation using multivariate analysis. Age, Abbreviated Injury Scale external, Glasgow Coma Scale on Emergency Department arrival, heart rate, and need for transfusion were independent predictors of failure to return to work at 6 months using multivariate analysis. Charlson Comorbidity Index, Glasgow Coma Scale on arrival, temperature, pain and need for inpatient rehabilitation were independent predictors of mortality at 6 months.

Major trauma is defined as having an Injury Severity Score (ISS) of Ōēź16, and may result from a range of mechanisms of injury from falls to motor vehicle accidents, industrial accidents, and assault [1,2]. The introduction of the Advanced Trauma Life Support program was a milestone in modern management of trauma patients and has been associated with reduced mortality across all levels of trauma severity [3]. Despite this, injury from trauma accounts for over 5 million deaths worldwide annually, and is the leading cause of mortality in individuals aged Ōēż 19 years [4,5].

However, the consequences of experiencing major trauma may be far-reaching, with the potential for long-term functional, psychological, physical, and economic sequalae [6ŌĆō9]. In patients with lower extremity fractures, less than half returned to work by 6 months and experienced prolonged disability [6]. Patients with chest trauma experience persistent reduced effort tolerance and decreased pulmonary-specific quality of life 6 months post discharge [7]. A quarter of patients who are admitted to the intensive care unit following major trauma develop acute kidney injury [8], and a quarter of adolescents develop long-term post-traumatic stress disorder post major trauma [9].

At present, despite the extensive number of studies reporting the negative effects of trauma, there is a paucity of studies that systemically investigate the effects of long-term trauma particularly in an Asian population, with existing studies [10ŌĆō14] limited by high dropout rates and short follow-up [2,15,16]. A more comprehensive understanding of patient outcomes is needed to guide the allocation of resources with the aim of minimizing long-term harm to patients. The aim of the study was to investigate functional recovery and patient reported outcomes at 6 months, including: return to work and ambulation status, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of self-assessed state of health, EuroQol-5 Dimension score and Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE).

A review was performed on the National Trauma Registry (NTR) database of consecutive major trauma patients admitted between 2016 and 2018 to a single Level 1 trauma center. Patients who were admitted from 2019 onwards were not included as their follow-up was confounded by the onset of the coronavirus disease pandemic in 2020. The NTR is a nationwide registry housed by the National Registry of Diseases Office, whose existence was mandated under the National Registry of Diseases Act. It archives data, prospectively collected, from all public hospital Emergency Department trauma cases and contains data pertaining to demographics, injury, presentation, treatment, and follow-up. Data collection was performed via chart reviews and interviews with patients and their caregivers at admission and 6 months post major trauma. Interviews were performed via phone by trained members of the NTR who had medical or nursing backgrounds. Three separate attempts were made to contact a patient or their caregiver before deeming them lost to follow-up. A further review at 12 months was performed if the patient has not returned to baseline at the 6-month review. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB no.: 2021/2497). All patients who suffered major trauma (defined as having ISS score Ōēź16), were included. No patients were excluded from the analysis.

Demographic data collected included age, gender, ethnicity, and premorbid medical conditions. Data related to the initial injury included the mechanism of injury, assessment on arrival to the Emergency Department, initial investigations, ISS, and Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS; 2015 version). Treatment related data included need for transfusion, procedures performed, median length of stay (LOS), complications, and need for rehabilitation. The long-term data collected included the patientsŌĆÖ residence, return to work, and ambulation status, VAS score of self-assessed state of health, EuroQol-5 Dimension score (2011 version), and GOSE were performed at 6 months.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows, Version 23.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics of demographic, injury, treatment, and outcome data was performed. Categorical data were presented as frequency (percentage), and continuous data were presented as the median (range) for non-parametric variables, and the mean (standard deviation) for parametric variables. Comparisons of the functional and quality of life scores were compared using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test and related-samples FriedmanŌĆÖs 2-way analysis of variance. Univariate analyses were performed to assess factors predicting failure to return to work, and ambulation, as well as mortality using the Mann Whitney U and Chi square test. Multivariate analysis was performed via binary regression on variables which yielded p < 0.05 on univariate analysis to assess for independent preoperative predictors of failure to return to work, and ambulation, and mortality.

Overall, 637 patients were treated for major trauma (ISS Ōēź 16) between 2016 to 2018 (Table 1). The median Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was 3 (range 0ŌĆō12). The most common mechanism of trauma was a fall from height (n = 360, 56.5%) followed by motor vehicle accident (n = 172, 27.0%). Assault, work-related accidents, self-harm and ŌĆ£otherŌĆØ accounted for 21 (3.3%), 15 (2.4%), 2 (0.3%), and 67 (10.5%), respectively. The median ISS was 24 (range 16ŌĆō75), and head injury was the most common (median AIS 4, range 0ŌĆō6).

On presentation, the median Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15 (range 3ŌĆō15), with normal median baseline parameters (Table 2). There were 152 (23.9%) patients who required transfusion and 18 (3.0%) underwent massive transfusion protocol. Surgery was performed in 274 (43.0%) patients and 183 (28.7%) required ICU admission. There were 27 (4.2%) patients who were pronounced dead in the Emergency Department. The median LOS was 10 days (range 0ŌĆō189) and 83 (12.9%) required inpatient rehabilitation. The median Functional Independence Measure score at discharge was 77 (n = 63, range 7ŌĆō124).

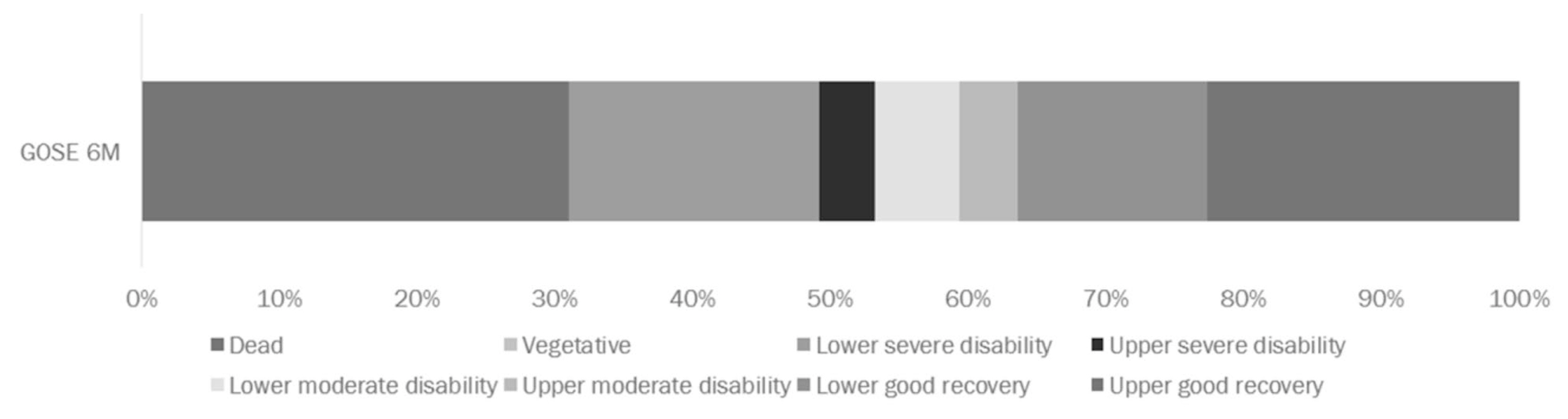

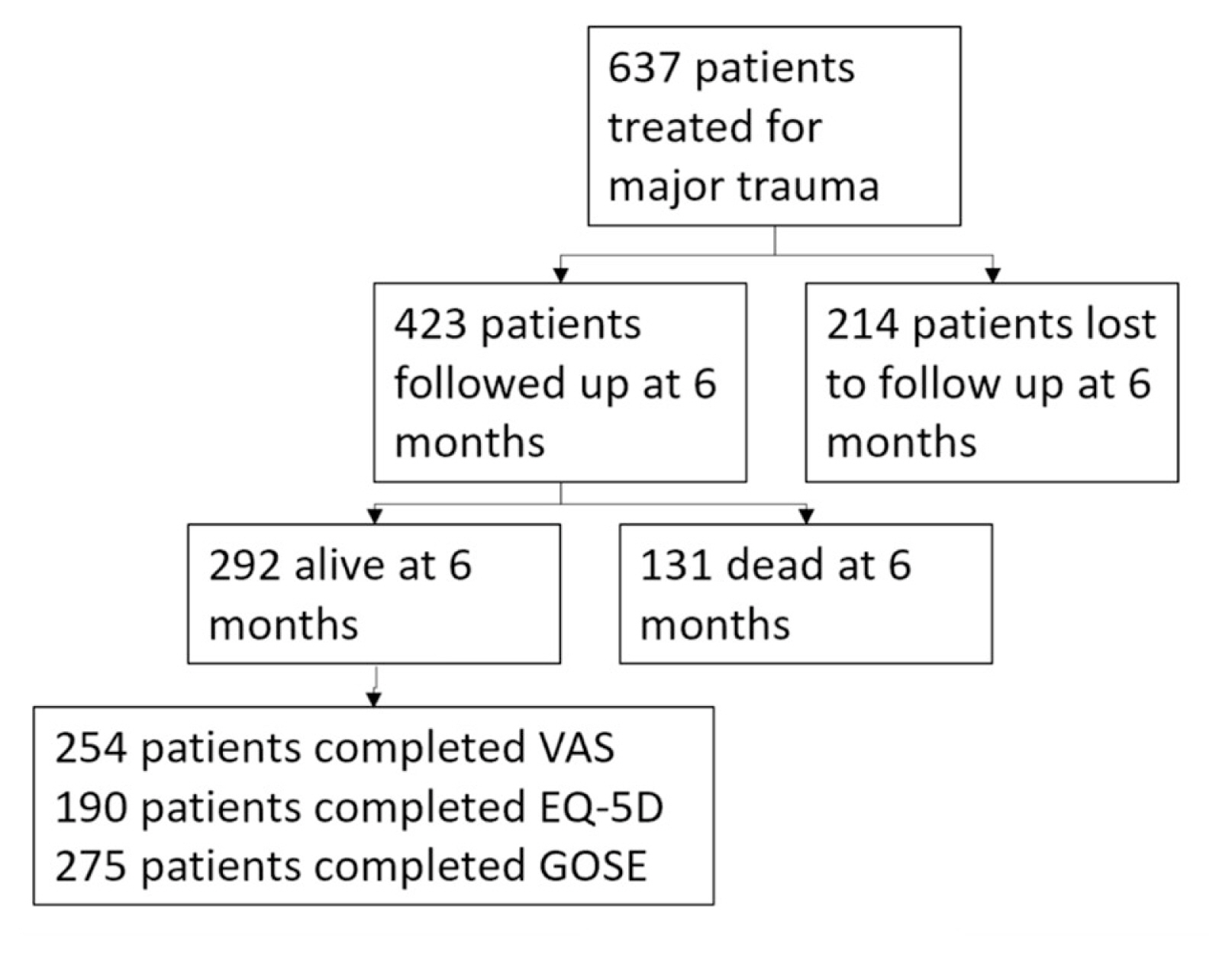

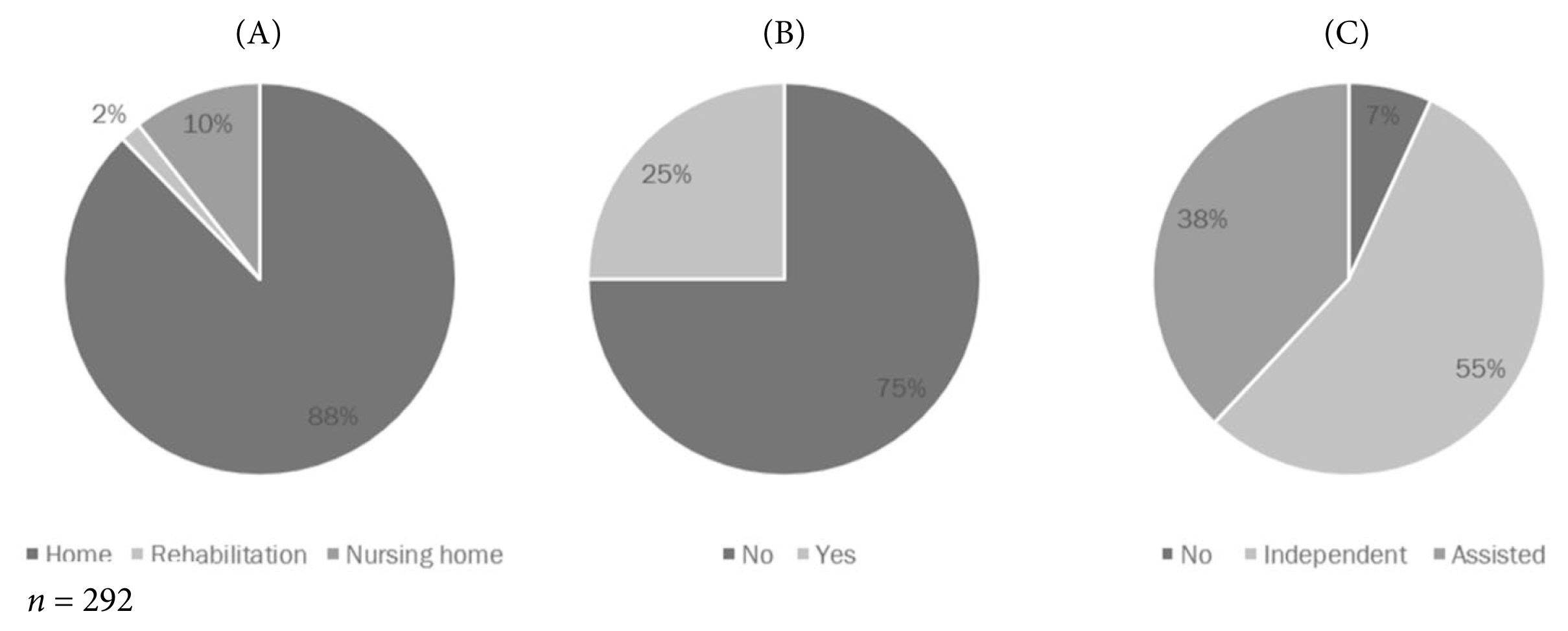

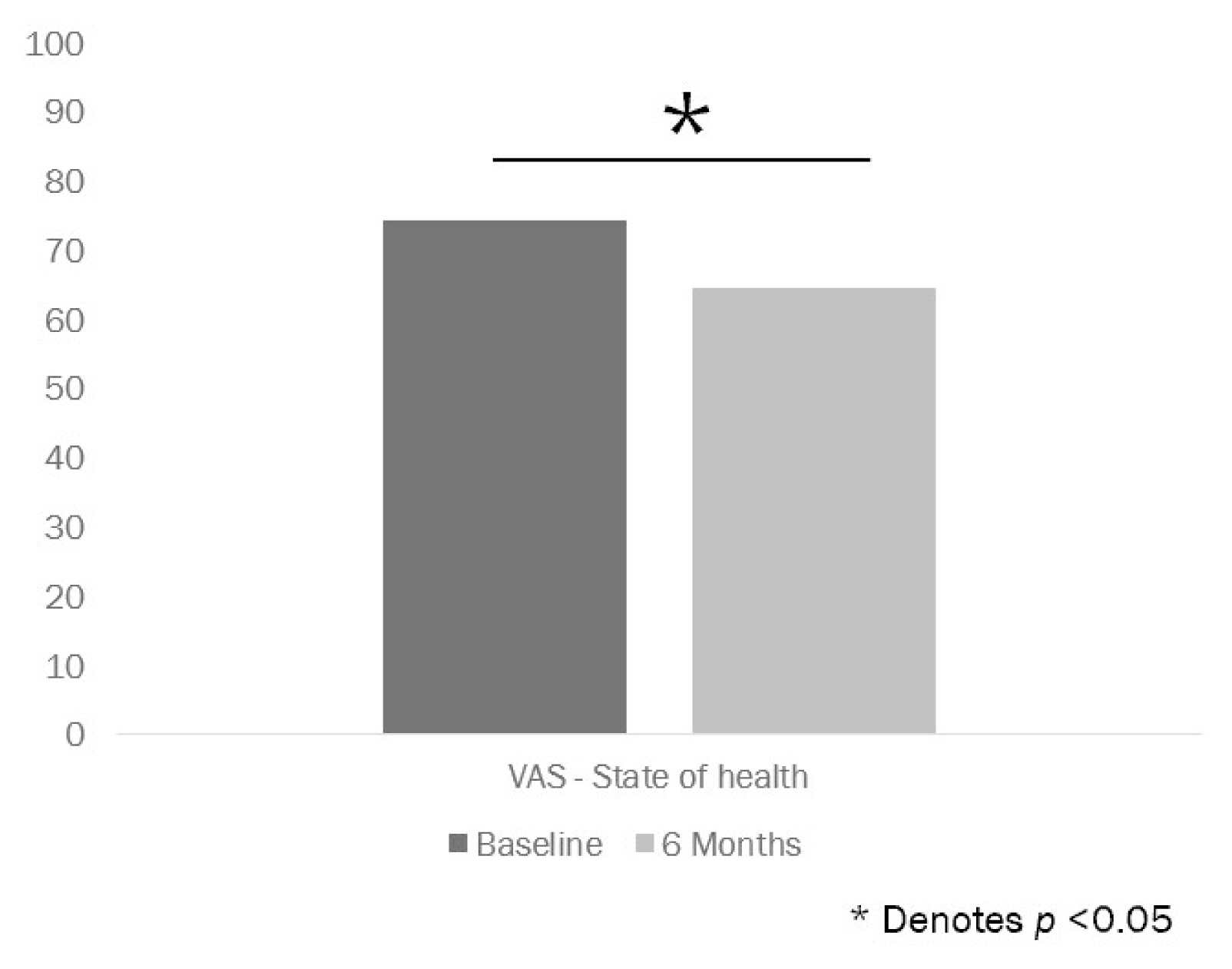

Of the 637 patients treated for major trauma, 423 (66.4%) patients were followed up at 6 months and 214 (33.6%) were lost to follow-up (Figure 1). Among the 423 patients followed up at 6 months, 292 patients were alive and 131 patients had died. Among the 292 survivors, 256 (87.6%) were living at home, 5 (1.7%) were living in rehabilitation facilities, and 31 (10.6%) resided in nursing homes (Figure 2). There were 73 (25.0%) of the respondents who worked prior to the injury, had returned to work. There were 161 (55.1%) who reported being able to ambulate with 111 (38.0%) who walked with assistance. Self-reported state of health using the VAS score of 254 respondents suggested a median score of 73 at baseline and 64 at 6 months (Figure 3). The EQD5 scores at 6 months are demonstrated in Figure 4, and GOSE scores at 6 months are demonstrated in Figure 5. Only 190 patients responded to the EQD5 questionnaire at 6 months, with the rest deceased or lost to follow-up. Only 275 patients were included in the analysis of GOSE scores at 6 months, with the rest being lost to follow-up.

Employing univariate analysis, age, ASA status, CCI, AIS head, AIS face, ISS, heart rate at admission, hemoglobin level, need for transfusion, LOS, inpatient complication, and Functional Independence Measure score at discharge were predictors of failure to return to ambulation in 6 months. Only age and LOS were significant independent predictors of return to ambulation using multivariate analysis (Tables 1 and 2).

Univariate analysis determined that age, race, ASA score, CCI, AIS head, AIS external, ISS, GCS on arrival, heart rate, SpO2, pain, hemoglobin, need for transfusion, or surgery were predictors of failure to return to work at 6 months. Using multivariate analysis, age, AIS external, GCS on arrival, heart rate, and need for transfusion were independent predictors of failure to return to work at 6 months (Tables 1 and 2).

Employing univariate analysis, age, ASA score, CCI, AIS head, AIS extremities, ISS, GCS on arrival, temperature, SpO2, pain, hemoglobin, base excess, lactate, need for transfusion, or surgery, LOS, and need for inpatient rehabilitation were predictors of mortality at 6 months. using multivariate analysis, CCI, GCS on arrival, temperature, pain, and need for inpatient rehabilitation were independent predictors of mortality at 6 months (Tables 1 and 2).

In this study, we aimed to investigate the long-term outcomes of patients following major trauma. The study was retrospectively performed in a Level 1 trauma center between 2016 and 2018. In this Asian background population, 6 months after major trauma, 1 in 10 patients were institutionalized, 3 in 4 patients had not returned to work, and 1 in 2 patients were unable to ambulate. Patients following major trauma had poor self-assessed state of health. In addition, 3 in 10 patients reported at least some problems with self-care, performing their usual activities, and experienced pain or discomfort. Of these patients 1 in 10 reported anxiety or depression at the 6-month follow-up. These findings are consistent with existing studies which demonstrate prolonged disability, delayed return to work, psychological sequalae, and chronic pain in patients who have experienced major trauma [6, 9,15,16].

This current study assessed outcomes in patients treated in a large tertiary hospital and the demographic makeup was reflective of the Singaporean population with a higher proportion of male patients [2]. The majority of patients were ASA 1 or 2 with a low median CCI. Most cases resulted from a fall from height or motor vehicle accident reflecting the metropolitan nature of the study setting. Despite the relative ŌĆ£healthinessŌĆØ of patients at presentation, they were not exempt from the lasting functional sequalae of major trauma such as delayed return to work, psychological distress, or chronic pain as observed previously [2].

Upfront mortality was low at 4.2%, reflective of the successes of a systematic approach to trauma as prescribed by the Advanced Trauma Life Support program [3]. As suspected, major trauma led to severe and often long-lasting effects for sufferers, with only 87.6% of responders still living at home after 6 months, 25.0% back to work, and 55.1% ambulating independently. For many patients, the single event of a traumatic accident represented a permanent change to their way of life, self-sufficiency, and agency. Their self-assessed state of health diminished significantly post major trauma. Self-care, getting back to their usual activities, and pain were issues at 6 months, with 25.6%, 28.7%, and 28.0% of patients, respectively, reporting at least some problem at 6 months. While patientsŌĆÖ assessment of anxiety and depression at 6 months was considerably low at 6.9%, an element of failure to report due to fear of stigmatization must be taken into account.

The ability to identify patients who would benefit from early rehabilitation is imperative, as is implementing the necessary processes to link a patient and their carers to the existing resources. It has been reported that patients aged over 75 years, a history of suicide attempts, AIS pelvis, AIS extremities, AIS spine, AIS head, ICU stay of over 3 days as well as need for intubation were predictive of a need for inpatient rehabilitation post severe trauma [17]. Similarly, pelvic injury, needing ICU admission, needing a neurosurgical operation, a fall from height, lower limb injury, and severe medical comorbidity were predictive of the need for rehabilitation post trauma [18].

In this current study, we observed that elderly patients who had prolonged LOS were less likely to return to ambulation at 6 months. This emphasizes the importance of engaging in rehabilitation early with an aim to maximize return to function to avoid a prolonged hospital stay. Trauma teams should bear this in mind when patients have been admitted to Emergency Departments and aim to promptly optimize the patientŌĆÖs analgesia to facilitate rehabilitation, particularly for frail patients. With analgesia optimized and acute medical issues resolved, patients may then be managed in a setting that allows for optimal rehabilitation with regular allied health intervention. In addition, elderly patients who had significant physiological responses to injury such as tachycardia, and low GCS on presentation as well as more severe external injuries, were less likely to return to work at 6 months.

Trauma teams may consider identifying such patients early and linking them up with medical social services as they may potentially lose their means to support themselves and dependents financially. The independent predictors of mortality identified (CCI, GCS on arrival, temperature, pain and need for inpatient rehabilitation) highlight the worse prognosis for those with significant premorbid conditions, fewer reserves, as well as neurological injuries [18].

The findings from this study highlight the importance of assigning resources well beyond admission and beyond rehabilitation. The multidomain nature of trauma recovery necessitates an early multidisciplinary approach involving rehabilitation physicians, social workers, psychologists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists. While surgeons, intensivists, and emergency physicians play an important role in the resuscitation of trauma victims, their input diminishes over time, and it is crucial to link up patients and their carers with the necessary expertise and long-term resources to assist recovery and return to normalcy.

Treating cancer with a multidisciplinary approach is the norm and a similar approach encompassing regular meetings/clinic visits to discuss coordinated care of major trauma victims could have significant benefit beyond 6 months. This could take the form of regular meetings involving stakeholders to discuss the needs and progress of patients who experienced major trauma. Moving forward, the rapid uptake of telemedicine may also be of use to regularly be in contact with patients who are undergoing rehabilitation post trauma to assess their needs [19].

A limitation of this study was the high dropout rate. As may be expected from conditions such as major trauma, patients with poor social support who are dependent for their activities of daily living may be less able to present for follow-up appointments or respond to phone consultation. This was despite multiple attempts by staff to contact the patients and their caregivers. The data presented in this study may potentially be an underestimate of severity of the impact on patients who have suffered major trauma, and may harbor responder bias between the patients who responded to follow-up versus those that were lost to follow-up. Also, this study drew from the data of the NTR, therefore, analyses were inherently limited by the type and quality of data recorded in the registry. For instance, information on the socioeconomic status, and income and number of dependents were not available, nor was the cause of death, which would have been useful for analyses. In addition, the data was limited to 6 months, potential longer-term trends post major trauma were not captured.

While a large study performed in Canada, North America [2] yielded similar findings when outcomes were assessed between 6 and 12 months, there has been no large-scale Asian study assessing long-term outcomes post major trauma. This current study offers a comprehensive, systematic assessment of long-term outcomes post major trauma managed in a Level 1 trauma center in Asia, and highlights the lasting functional deficits needing rehabilitation. This can be viewed as a blind-spot in delivery of trauma care in Singapore and the results highlight the need to allocate resources urgently in this area.

Moving forward, studies would be required to assess the effects of trauma beyond 6 months. In particular, studies assessing the impact of early rehabilitation and role of social work, psychology, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and pain management services would be of most use, as would studies that establish the benefit of having a multidisciplinary team approach beyond discharge. With the rapid uptake of telemedicine, further studies could assess its role in optimizing recovery. Other domains such as caregiver stress and the economic impact of trauma would also benefit from further research.

In summary, patients face poor functional outcomes after experiencing severe trauma, with low rates of return to independent ambulation, and work. Severity of injury, in particular injury to the head, chest, and abdomen, was predictive of failure to return to work in 6 months. These patients would benefit from early rehabilitation which requires a team-based approach well beyond the discharge.

Notes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: YLL and SM. Data curation: YLL, SM, HWJ, STC, PLC, and NMJ. Formal analysis: YLL. Funding acquisition: NIL. Investigation: YLL, SM, FTTP, STC, PLC, and NMJ. Methodology: YLL, SM, HWJ, STC, PLC, and NMJ. Project administration: SM, STC, PLC, and NMJ. Resources: SM, STC, PLC, and NMJ. Supervision: SM. Validation: SM. Visualization: YLL and SM. Writing ŌĆō original draft: YLL and SM. Writing ŌĆō review & editing: YLL, SM, HWJ, STC, PLC, and NMJ.

Figure┬Ā1

Outcomes of patients 6 months post major.

EQ-5D = EuroQoL-5 dimension; GOSE = Glasgow outcome scale extended; VAS = visual analogue scale.

Figure┬Ā2

Disposition of patients 6 months post major trauma.

(A) Residence. (B) Return to work. (C) Return to ambulation.

Figure┬Ā3

VAS score indicating perceived state of health at baseline and 6 months.

VAS = visual analogue scale.

Table┬Ā1

Demographic and injury characteristics and univariate and multivariate analysis to determine factors associated with return to ambulation, return to work, and death

| Characteristic (N = 637) | Median (range)/n (%) | Predictor of return to ambulation (6 mo) | Predictor of return to work (6 mo) | Predictor of death (6 mo) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | OR (95% CI) | Univariate | Multivariate | OR (95% CI) | Univariate | Multivariate | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Demographics | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Age (y) | 64 (16ŌĆō100) | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | 1.04 | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | 1.05 | < 0.05* | 0.34 | 1.01 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Sex (male) | 435 (68.3) | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.30 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Race | 0.53 | 0.03* | 0.33 | 3.50 | 0.48 | |||||

| ŌĆāChinese | 483 (75.8) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāIndian | 55 (8.6) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāMalay | 49 (7.7) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāOthers | 50 (7.8) | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| ASA | < 0.05* | 0.09 | 1.84 | < 0.05* | 0.69 | 1.25 | < 0.05* | 0.36 | 1.39 | |

| ŌĆā1 | 270 (42.4) | |||||||||

| ŌĆā2 | 152 (23.9) | |||||||||

| ŌĆā3 | 215 (33.8) | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| CCI | 3 (0ŌĆō12) | < 0.05* | 0.67 | 1.05 | < 0.05* | 0.81 | 1.03 | < 0.05* | 0.01* | 1.31 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Injury | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Mechanism | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| ŌĆāFall from a height | 360 (56.5) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāMotor vehicle accident | 172 (27.0) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāOthers | 67 (10.5) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāAssault | 21 (3.3) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāIndustrial/work-related | 15 (2.4) | |||||||||

| ŌĆāSelf-harm | 2 (0.3) | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| AIS | ||||||||||

| ŌĆāHead | 4 (0ŌĆō6) | 0.04* | 0.41 | 1.08 | < 0.05* | 0.28 | 1.15 | < 0.05* | 0.29 | 1.17 |

| ŌĆāFace | 0 (0ŌĆō4) | 0.04* | 0.08 | 1.37 | 0.13 | 0.72 | ||||

| ŌĆāChest | 0 (0ŌĆō6) | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.16 | ||||||

| ŌĆāAbdomen | 0 (0ŌĆō5) | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.11 | ||||||

| ŌĆāExternal | 1 (0ŌĆō6) | 0.06 | 0.01* | 0.02* | 1.74 | 0.43 | ||||

| ŌĆāExtremities | 0 (0ŌĆō5) | 0.26 | 0.60 | < 0.05* | 0.14 | 1.35 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| ISS | 24 (16ŌĆō75) | 0.04* | 0.20 | 1.03 | < 0.05* | 0.24 | 1.03 | < 0.05* | 0.46 | 1.01 |

Table┬Ā2

Presentation and treatment characteristics and univariate and multivariate analysis to determine factors associated with return to ambulation, return to work, and death

| Characteristic (N = 637) | Median (range) / n (%) | Predictor of return to ambulation (6 mo) | Predictor of return to work (6 mo) | Predictor of death (6 mo) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | OR (95% CI) | Univariate | Multivariate | OR (95% CI) | Univariate | Multivariate | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Presentation | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Admission parameters | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| ŌĆāGCS | 15 (3ŌĆō15) | 0.27 | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | 1.24 | < 0.05* | 0.01* | 1.10 | ||

| ŌĆāSystolic BP (mmHg) | 137 (0ŌĆō235) | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.13 | ||||||

| ŌĆāHeart rate (bpm) | 84 (0ŌĆō180) | 0.02* | 0.06 | 1.01 | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | 1.03 | 0.64 | ||

| ŌĆāTemperature (┬║C) | 36.5 (0ŌĆō40) | 0.96 | 0.10 | < 0.05* | 0.01* | 1.64 | ||||

| ŌĆāRR | 18 (0ŌĆō40) | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.19 | ||||||

| ŌĆāSpO2 | 98 (0ŌĆō100) | 0.16 | 0.01* | 0.46 | 1.05 | 0.03* | 0.40 | 1.01 | ||

| ŌĆāPain | 0 (0ŌĆō10) | 0.41 | < 0.05* | 0.95 | 1.00 | < 0.05* | 0.01* | 1.17 | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| Initial investigations | ||||||||||

| ŌĆāHemoglobin | 12.5 (4.8ŌĆō19.7) | 0.01* | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | ||||||

| ŌĆāPlatelet | 133.5 (18ŌĆō551) | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.28 | ||||||

| ŌĆāBase excess | ŌłÆ3.1 (ŌłÆ33.9ŌĆō53) | 0.27 | 0.76 | 0.03* | ||||||

| ŌĆāLactate | 2.7 (0.4ŌĆō28) | 0.44 | 0.08 | < 0.05* | ||||||

| ŌĆāCreatinine kinase | 337 (3.7ŌĆō20,000) | 0.02* | 0.22 | 0.57 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Treatment | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Need for MTP | 18 (3.0) | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.14 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Need for transfusion | 152 (23.9) | < 0.05* | 0.11 | 1.71 | < 0.05* | 0.02* | 3.53 | < 0.05* | 0.29 | 1.41 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Need for surgery | 274 (43.0) | 0.50 | < 0.05* | 0.45 | 1.35 | < 0.05* | 0.17 | 1.60 | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| Need for ICU | 183 (28.7) | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.01* | 0.10 | 1.87 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Length of stay (d) | 10 (0ŌĆō189) | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | 1.05 | 0.06 | < 0.05* | 0.96 | 1.00 | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| Need for inpatient rehabilitation | 83 (12.9) | 0.78 | 0.20 | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | 4.87 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Inpatient complication | 82 (12.9) | 0.03* | 0.92 | 1.02 | 0.58 | 0.90 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| FIM score at discharge | 77 (7ŌĆō124) | 0.01* | 0.10 | 6.66 | 0.17 | 0.88 | ||||

References

1. Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 1974;14(3):187ŌĆō96.

2. Laupland KB, Kortbeek JB, Findlay C, Hameed SM. A population-based assessment of major trauma in a large Canadian region. Am J Surg 2005;189(5):571ŌĆō6.

3. Ali J, Adam R, Butler AK, Chang H, Howard M, Gonsalves D, et al. Trauma outcome improves following the advanced trauma life support program in a developing country. J Trauma 1993;34(6):890ŌĆō9.

4. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380(9859):2095ŌĆō128.

5. Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson JP. Long-term posttraumatic stress disorder persists after major trauma in adolescents: new data on risk factors and functional outcome. J Trauma 2005;58(4):764ŌĆō71.

6. MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med 2006;354(4):366ŌĆō78.

7. Leone M, Br├®geon F, Antonini F, Chaumo├«tre K, Charvet A, Ban LH, et al. Long-term outcome in chest trauma. Anesthesiology 2008;109(5):864ŌĆō71.

8. Eriksson M, Brattstr├Čm O, M├źrtensson J, Larsson E, Oldner A. Acute kidney injury following severe trauma: Risk factors and long-term outcome. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79(3):407ŌĆō12.

9. Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson JP. Long-term posttraumatic stress disorder persists after major trauma in adolescents: new data on risk factors and functional outcome. J Trauma 2005;58(4):764ŌĆō71.

10. Kakkos SK, Tyllianakis M, Panagopoulos A, Kokkalis Z, Lianou I, Koletsis E, et al. Outcome predictors in civilian and iatrogenic arterial trauma. World J Surg 2021;45(1):160ŌĆō7.

11. Engelmann EWM, Wijers O, Posthuma J, Schepers T. Management and outcome of hindfoot trauma with concomitant talar head injury. Foot Ankle Int 2021;42(6):714ŌĆō22.

12. Albin CB, Feema R, Aparna L, Darpanarayan H, Chandran J, Abhilash KPP. Paediatric trauma aetiology, severity and outcome. J Family Med Prim Care 2020;9(3):1583ŌĆō8.

13. Belmonte-Grau M, Garrido-Ceca G, Marticorena-├ülvarez P. Ocular trauma in an urban Spanish population: epidemiology and visual outcome. Int J Ophthalmol 2021;14(9):1327ŌĆō33.

14. O'Reilly DA, Bouamra O, Kausar A, Malde DJ, Dickson EJ, Lecky F. The epidemiology of and outcome from pancreatoduodenal trauma in the UK, 1989ŌĆō2013. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015;97(2):125ŌĆō30.

15. Redmill DA, McIlwee A, McNicholl B, Templeton C. Long term outcomes 12 years after major trauma. Injury 2006;37(3):243ŌĆō6.

16. Herrera-Escobar JP, Osman SY, Das S, Toppo A, Orlas CP, Castillo-Angeles M, et al; National Trauma Research Action Plan (NTRAP) Investigators Group. Long-term patient-reported outcomes and patient-reported outcome measures after injury: the National Trauma Research Action Plan (NTRAP) scoping review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;90(5):891ŌĆō900.

17. Debus F, Lefering R, Lang N, Oberkircher L, Bockmann B, Ruchholtz S, et al. Which factors influence the need for inpatient rehabilitation after severe trauma? Injury 2016;47(12):2683ŌĆō7.